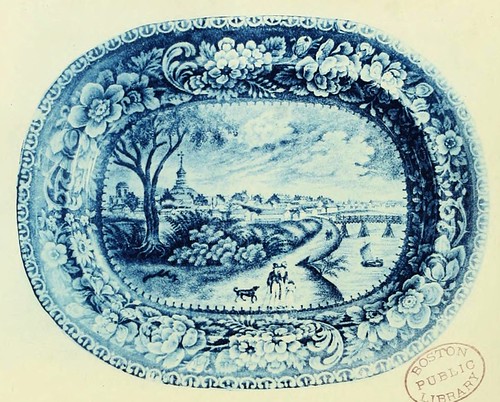

"Chillicothe with Cows" Staffordshire platter. Used courtesy of Prices 4 Antiques.

In the early through mid 19th century, a considerable volume of Staffordshire pottery was created with views of American scenes. They were created, in Staffordshire, for the United States audience. Four illustrate Ohio views: two of Chillicothe, the first capitol of the state; and one each of Sandusky and Columbus.

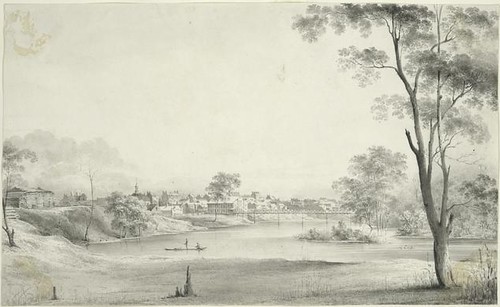

Sandusky Staffordshire platter. Reproduced from Pictures of early New York on dark blue Staffordshire pottery, together with pictures of Boston and New England, Philadelphia, the South and West (1899) by R.T. Haines Halsey. Used courtesy of Boston Public Library and the Internet Archive.

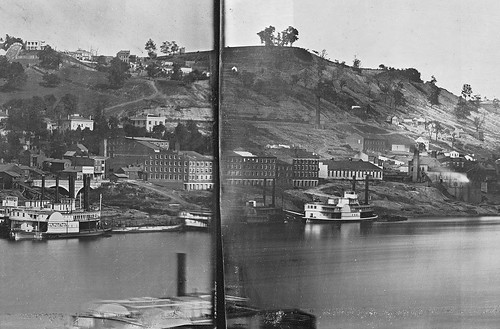

There's little doubt that the Sandusky platter does, in fact, illustrate Sandusky, Ohio. It's consistent enough what was known about the city at the time that we can be confident in this assumption.

Columbus Staffordshire platter. Reproduced from Pictures of early New York on dark blue Staffordshire pottery, together with pictures of Boston and New England, Philadelphia, the South and West (1899) by R.T. Haines Halsey. Used courtesy of Boston Public Library and the Internet Archive.

Likewise, we can say the same for this view of Columbus. It illustrates the city from a viewpoint similar to that used by Thomas Kelah Wharton, below.

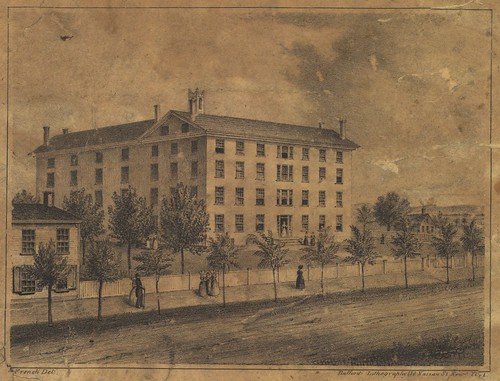

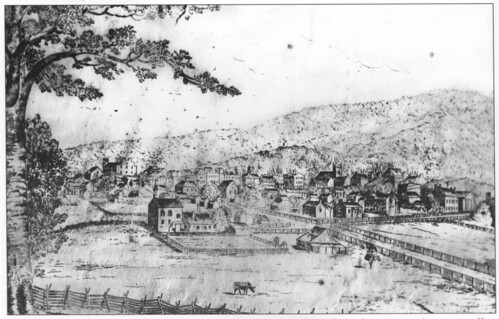

Columbus, Ohio from the south west. A drawing (1832) by Thomas Kelah Wharton. Used courtesy of the New York Public Library.

The similar in the lay of the city in Wharton's viewpoint, from the southwest, would seem to suggest that both views were made near the same time.

The two Chillicothe views - the one illustrated above and Chillicothe with raft - have, to this point, presented more difficulty. The most obvious landmark, the first statehouse, isn't visible in either view. It's been suggested by many that these views might not be Chillicothe at all, but rather, some other images chosent to stand in.

I tend to be cautious about asserting that a view isn't a place without evidence as to the actual location of the view being depicted. For an example of the dangers of these assumptions, I need point no further than Karl Bodmer's print of the Cleveland lighthouse, which many asserted couldn't be Cleveland because the lighthouse was clearly different and had different surroundings. It turned out that the structure being depicted was the harbor light, as is illustrated in depth in New Find! First* Painting of Cleveland in Color!

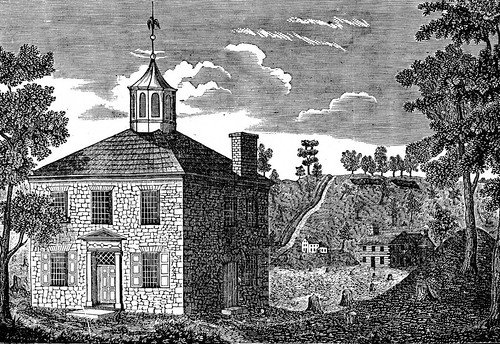

S.W. View of Chillicothe. An engraving (1839) by Charles Foster. Reproduced from Chillicothe, Ohio by G. Richard Peck. Used courtesy of the Ross County Historical Society.

The landscape illustrated in the Staffordshire platter of Chillicothe seemed inconsistent with the one shown in this 1839 engraving by Charles Foster, one of four views of the city that he printed that year. This made me less comfortable with the assumption that the view on the platter was, in fact, Chillicothe, Ohio.

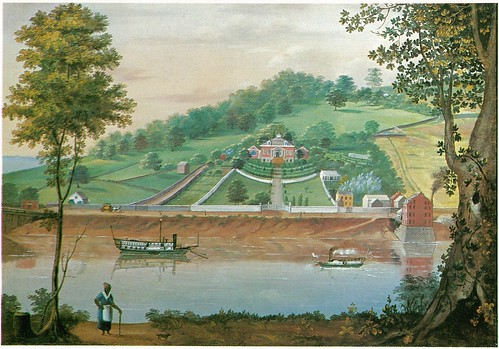

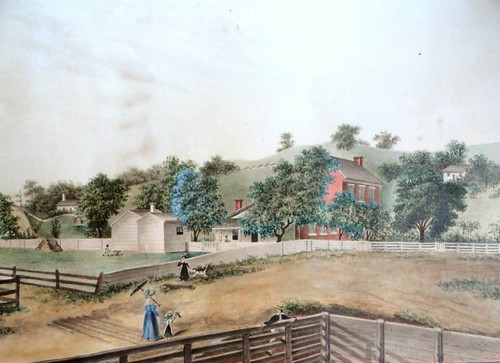

George Wood residence, Chillicothe, Ohio. A watercolor painting (late 1830s). Used courtesy of Donald Carpentier.

A couple weeks ago, my colleague, Andrew Richmond, asked me if I might be able to identify the house illustrated in this watercolor from the late 1830s, the residence of one George Wood. I dug in. While Wood was clearly a man of considerable means, I wasn't able to learn that much about him. I was able to narrow down the general location of the residence, but beyond that, I was unsure. What followed was a lot of hemming and hawing.

Finally, I sent an email to Pat Medert, Archivist, at the Ross County Historical Society. Her response was most illuminating: "The house in the painting appears to be that of George Wood who resided at 144 W. Fifth St. George was born in 1793 in Jefferson County, VA. The family moved to Kentucky when he was a child, and in 1810, he and his brother, John moved to Chillicothe. They were partners in the mercantile and pork packing businesses. George also invested extensively in farm land in Ross County and was a person of considerable wealth at the time of his death in January 1861. He was never married and his estate went to his sister, Susan Hoffman."

Medert added, "George bought the property in 1833 and erected the house in 1837. It can be seen in a sketch made by Charles Foster in 1839. The house was remodeled in 1874, and renovations included the construction of an addition to the east side of the house. It is still standing and is well maintained."

(The George Wood residence is about a third of the way from the left in the Charles Foster print.)

The George Wood residence is on the south side of the street. The surrounding geology means that this view is looking approximately southwest.

This is, indeed, an interesting painting, but what does it have to do with the Staffordshire Chillicothe (with cows)?

Look at the background of the George Wood residence. The hills aren't covered with trees like they are in the Charles Foster print. Further, they're similar in style to the view on Chillicothe (with cows). This suggested to me, "Hey, this might actually be Chillicothe, Ohio."

With the assumption that the view on this piece of Staffordshire was Chillicothe, I tested what would happen if one made the rest of the evidence fit that hypothesis.

Chillicothe Courthouse, Etc., in 1801. A print (June, 1842) by Horace C. Grosvenor. Published in American Pioneer (June, 1842). Used courtesy of the Ohio Historical Society.

This is the first statehouse, as illustrated in 1842. At the time, the building was still standing - this represents a reasonably accurate depiction of the structure. The statehouse was in the middle of this city. What this illustration doesn't convey are the significant quantity of buildings that were built up around the structure by the 1830s.

Since the statehouse was only two stories tall, it wouldn't stand out much among the buildings.

Chillicothe with cows (detail). A Staffordshire platter (circa 1830). Used courtesy of Dennis and Dad Antiques.

With the assumption that this is Chillicothe, the statehouse is most likely represented by the cupola indicated by the green arrow. With that knowledge, how can we orient ourselves in this city?

The 1860 Topographical map of Ross County, Ohio includes the first detailed map of Chillicothe that I've been able to find. Note: if you're aware of an earlier one, please let me know. The lack of such a map seems odd, especially given that one of the great early maps of the state, Hough and Bourne's 1815 Map of the State of Ohio was published there.

The 1860 map doesn't help much. The landscape illustrated in the foreground, which I assumed was the floodplain of the Scioto River, had been significantly changed since the view used for the Staffordshire platter was made.

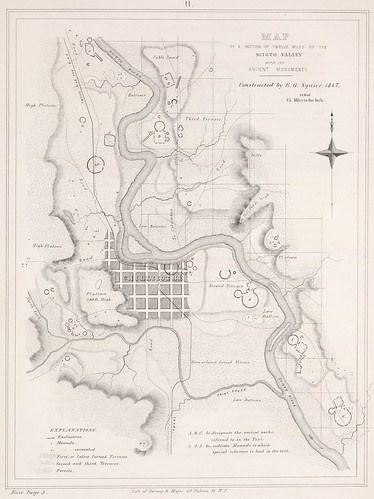

Map of a Section of Twelve Miles of the Scioto Valley with its Ancient Monuments. Constructed by E.G. Squier, 1847. A print (June, 1847) by Sarony and Major. Plate II in Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley (June, 1847) by Ephraim G. Squier and Edwin H. Davis. Used courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

In a desperate measure for any sort of early map of the city at all, I remembered this wonderful view from Squier and Davis' 1847 Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley. It illustrates all of the Native American earthworks present in the vicinity of Chillicothe, most of which are now lost.

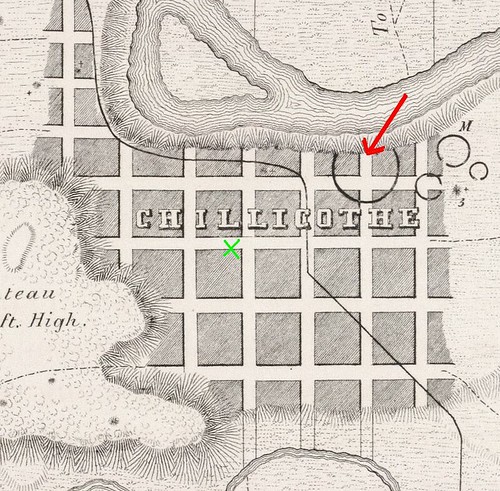

Detail, Map of a Section of Twelve Miles of the Scioto Valley with its Ancient Monuments. Constructed by E.G. Squier, 1847. A print (June, 1847) by Sarony and Major. Plate II in Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley (June, 1847) by Ephraim G. Squier and Edwin H. Davis. Used courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

This detail illustrates the area being illustrated. In the lower left are the hills we see in the background. The green "X" marks the approximate location of the statehouse. The artist's viewpoint is marked by a red arrow.

The cows, then, it seems, are sitting inside a circular mound! What better visual icon could there be for that area, really, than the earthworks built by the Native Americans?

Not only does this information help to reasonably conclude that the view is, indeed, Chillicothe, Ohio, but it means that we now have an image of a Native American earthwork that before this point we knew only by a measured drawing!

![1885-07-13-Page1]](http://farm6.staticflickr.com/5335/8766195163_b199fb9fc0.jpg)

![[Granville Female College]](http://farm9.staticflickr.com/8550/8703957989_9b11da87b4.jpg)