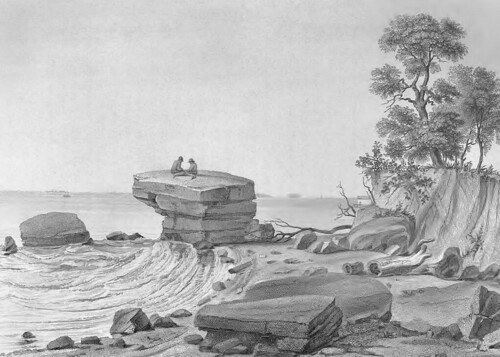

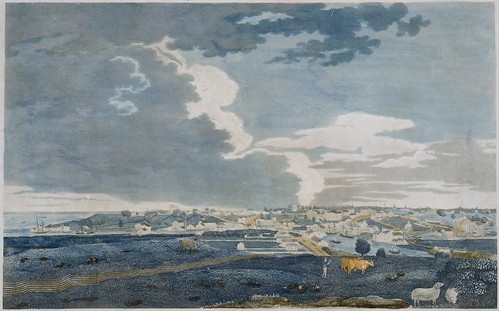

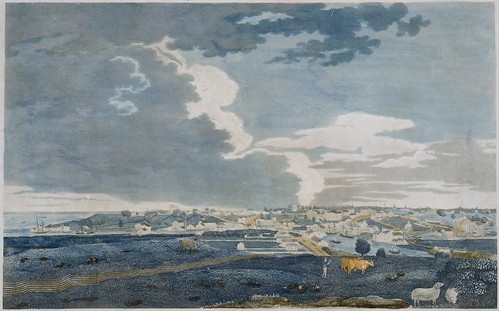

Lake Erie, From Cleveland. A watercolor painting (July, 1833) by Seth Eastman. Used courtesy of Sloans and Kenyon Auctioneers and Appraisers, Bethesda, Maryland.

Lake Erie, From Cleveland. A watercolor painting (July, 1833) by Seth Eastman. Used courtesy of Sloans and Kenyon Auctioneers and Appraisers, Bethesda, Maryland.

When I think about downtown Cleveland and the mouth of the Cuyahoga, images of industry and commerce come to mind. While I know it wasn't always this way, this area has so long been the heart of the city it's hard to imagine it otherwise. Even

Thomas Whelpley's four views of the city, published in 1834, show a quickly-growing city.

It's for that very reason that this watercolor, made by Seth Eastman in July, 1833, is so special - it represents the earliest detailed painting I'm aware of of the mouth of the Cuyahoga River.

Eastman probably came through Cleveland en route from

Fort Snelling, in Minnesota, to

West Point, New York, where he had received a teaching appointment. He appears to have been looking west from what is now

the intersection of West Sixth Streets and Lakeside Avenue.

In the foreground, to the right, there's a group of five Native Americans, said to be Iroquois. A few people sit on the hillside, where a row of fenceposts is visible. Closer to the river are a couple of buildings, one of which appears to be a log house. On the river, there are what could be canal boats. The pier and harbor light are also present. The hill at the mouth of the Cuyahoga, on the west bank, had not yet been flattened. A steamship, with a cloud of black smoke, sails on Lake Erie. In the distance, we see what would come to be called the "Gold Coast."

These things are all significant.

There are almost no historic images of Native Americans in Ohio. Of those, virtually all were either made years after the fact, based on memory and conjecture or were made by artists who hadn't seen the people in question. I can't think of another painting (within the scope of my current research - before 1866) that documents Native Americans in Ohio

at the time the painting was made.

The presence of a log building is also notable - there are very few known in northern Ohio. While there were a good number built (though not in such numbers as in the southern part of the state) they would have usually been covered with siding as soon as was practical, as a matter of fashion and appearance.

Further, this painting documents Cleveland at a point just before it underwent a major transformation. With the completion of the Ohio and Erie Canal, Cleveland and the interior of Ohio were opened up to commerce. The cost of shipping goods dropped considerably. Cuyahoga County's population would more than double between 1830 and 1840. It would almost double again by 1850. The landscape illustrated here would soon be gone.

Cleveland, 1853 A hand colored lithograph (1853) by B.F. Smith, after a drawing by J.W. Hill. Published by Smith Bros. & Co. Used courtesy of the Chicago Historical Society. Reproduced from Bird's Eye Views: Historic Lithographs of North American Cities by John W. Reps.

Cleveland, 1853 A hand colored lithograph (1853) by B.F. Smith, after a drawing by J.W. Hill. Published by Smith Bros. & Co. Used courtesy of the Chicago Historical Society. Reproduced from Bird's Eye Views: Historic Lithographs of North American Cities by John W. Reps.

This view, made 20 years later, from the west bank of the Cuyahoga, looking east, shows the magnitude of the change. While the west bank still has plenty of vacant land, the east side and downtown are mostly built up. Warehouses line the banks of the Cuyahoga River. To the right, we see both the Cuyahoga River and the narrower Ohio and Erie Canal.

Cleveland, Ohio, From Brooklyn Hill Looking East. A hand-colored etching (1834) by Thomas Whelpley. Engraved by Milo Osborne. Used courtesy of Cleveland Public Library.

Cleveland, Ohio, From Brooklyn Hill Looking East. A hand-colored etching (1834) by Thomas Whelpley. Engraved by Milo Osborne. Used courtesy of Cleveland Public Library.

The point from where Seth Eastman made the watercolor is illustrated in this 1834 print,

Cleveland, Ohio, From Brooklyn Hill Looking East.

Detail, Cleveland, Ohio, From Brooklyn Hill Looking East. A hand-colored etching (1834) by Thomas Whelpley. Engraved by Milo Osborne. Used courtesy of Cleveland Public Library.

Detail, Cleveland, Ohio, From Brooklyn Hill Looking East. A hand-colored etching (1834) by Thomas Whelpley. Engraved by Milo Osborne. Used courtesy of Cleveland Public Library.

This detail, taken from the left side of the print, illustrates the location more clearly. Eastman's vantage point is indicated by the red arrow. Note the row of fenceposts, illustrated in the painting, to the left of the arrow. The yellow arrow indicates the location of the Cleveland lighthouse.

Detail, Lake Erie, From Cleveland. A watercolor painting (July, 1833) by Seth Eastman. Used courtesy of Sloans and Kenyon Auctioneers and Appraisers, Bethesda, Maryland.

Detail, Lake Erie, From Cleveland. A watercolor painting (July, 1833) by Seth Eastman. Used courtesy of Sloans and Kenyon Auctioneers and Appraisers, Bethesda, Maryland.

It's worth noting the presence of the harbor light, at the mouth of the Cuyahoga River. This structure was likely completed a year or two earlier.

![[Cleveland harbor]](http://farm9.staticflickr.com/8516/8414635606_e3049f77d0.jpg) [Cleveland harbor] A print (1837) by Charles Whittlesey. Published in the Annual report on the geological survey of the State of Ohio (1837). Used courtesy of Ohio State University and the Internet Archive.

[Cleveland harbor] A print (1837) by Charles Whittlesey. Published in the Annual report on the geological survey of the State of Ohio (1837). Used courtesy of Ohio State University and the Internet Archive.

The pier upon which the harbor light was built is illustrated, top and center, in this drawing - letter "F". There's a square, on the right (east) side of the river that provided the foundation for the structure.

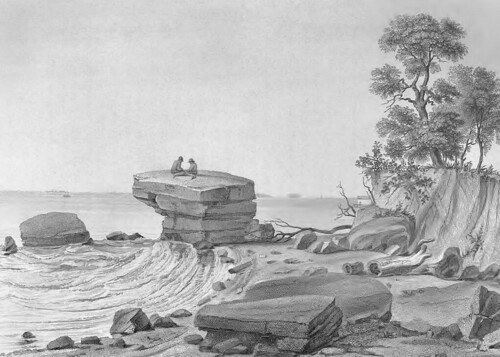

Cleveland Lighthouse on the Lake Erie. A hand-colored engraving (1839) by Pierre Eugène I. Aubert, after a drawing by Karl Bodmer. Published in Reise in das innere Nord-America in den Jahren 1832 bis 1834 (1839) by Maximilian Wied. Used courtesy of the Beinecke Library, Yale University.

Cleveland Lighthouse on the Lake Erie. A hand-colored engraving (1839) by Pierre Eugène I. Aubert, after a drawing by Karl Bodmer. Published in Reise in das innere Nord-America in den Jahren 1832 bis 1834 (1839) by Maximilian Wied. Used courtesy of the Beinecke Library, Yale University.

I've often heard suggested that this 1839 print, based on preliminary drawings and/or paintings made in 1834, doesn't actually portray the Cleveland lighthouse. What then, I ask, does it portray? The response tends to be a mumble that it's probably somewhere else.

It's been pointed out that the structure in the print doesn't look like the Cleveland lighthouse, nor is it located up on the hill like the Cleveland lighthouse was - see the point noted by the yellow arrow above.

Seth Eastman's painting, combined with Charles Whittlesey's map of the harbor seem to indicate that Karl Bodmer's print,

Cleveland Lighthouse on the Lake Erie, does, in fact, depict a Cleveland scene. It's just that the structure being illustrated isn't the lighthouse but rather, the harbor light. Perhaps this was a translation issue.

Bodmer's vantage point appears to have been from the west bank of the Cuyahoga. It's worth noting that the physical relationship between the ship and the harbor light appears to be about the same in Seth Eastman's painting and Karl Bodmer's print. What does this mean? I do not know.

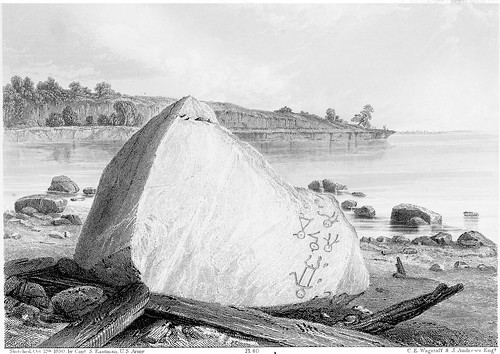

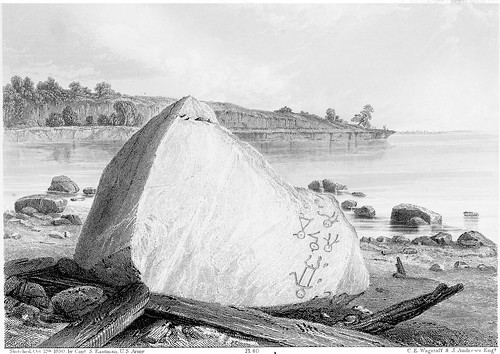

View of Inscription Rock on South side of Cunningham Island, Lake Erie. A print (1852) The print is based on a drawing by Seth Eastman created in 1850.

View of Inscription Rock on South side of Cunningham Island, Lake Erie. A print (1852) The print is based on a drawing by Seth Eastman created in 1850.

C. E. Wagstaff & J. Andrews (Engraver) Published in Historical and statistical information respecting the history, condition, and prospects of the Indian tribes of the United States; collected and prepared under the direction of the Bureau of Indian Affairs per act of Congress of March 3rd, 1847, Volume 2 (1852) by Henry Rowe Schoolcraft. Image used courtesy of the Ohio Historical Society.

Seth Eastman is best known for the work he did portraying Native Americans - the greatest bulk of which appeared in Henry Rowe Schoolcraft's

Historical and Statistical Information, Respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States, published in the 1850s. This view of Kelley's Island is one such image.

Sculptured Inscriptions on Rock, South Side Of Cunningham's Island, Lake Erie. A pen and ink drawing (October 10, 1850) by Seth Eastman. Reproduced from Seth Eastman: A Portfolio of North American Indians (1995) by Sarah E. Boehme, Christian F. Feest, and Patricia Condon Johnston.

Sculptured Inscriptions on Rock, South Side Of Cunningham's Island, Lake Erie. A pen and ink drawing (October 10, 1850) by Seth Eastman. Reproduced from Seth Eastman: A Portfolio of North American Indians (1995) by Sarah E. Boehme, Christian F. Feest, and Patricia Condon Johnston.

His record of Inscripion Rock on Kelley's Island, the original drawing for which is shown here, remains the best document that we have of this important, but now rather eroded, pictograph group.

Inscription Rock, North Side of Cunningham's Is., Lake Erie. A print (1852) by Seth Eastman, from a sketch made October 12, 1850. Published in Historical and statistical information respecting the history, condition, and prospects of the Indian tribes of the United States; collected and prepared under the direction of the Bureau of Indian Affairs per act of Congress of March 3rd, 1847, Volume 2 (1852) by Henry Rowe Schoolcraft. Used courtesy of Cornell University Library and the Internet Archive.

Inscription Rock, North Side of Cunningham's Is., Lake Erie. A print (1852) by Seth Eastman, from a sketch made October 12, 1850. Published in Historical and statistical information respecting the history, condition, and prospects of the Indian tribes of the United States; collected and prepared under the direction of the Bureau of Indian Affairs per act of Congress of March 3rd, 1847, Volume 2 (1852) by Henry Rowe Schoolcraft. Used courtesy of Cornell University Library and the Internet Archive.

Another boulder, now lost, inscribed with pictographs was present on the north shore of Kelley's Island, near the present state park campground.

Eastman's documentation of the island also included

two earthworks.

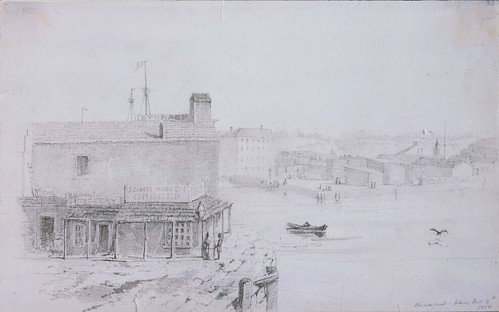

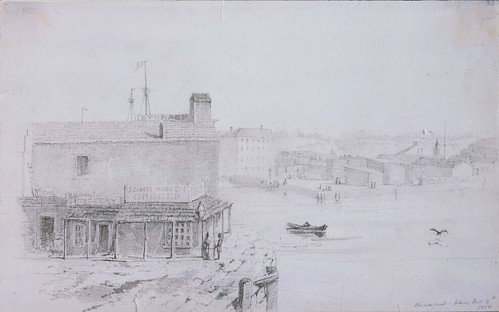

Cleveland, Ohio Grocery Store [John Smith Grocer]. A drawing (October 9, 1850) by Seth Eastman. Used courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Cleveland, Ohio Grocery Store [John Smith Grocer]. A drawing (October 9, 1850) by Seth Eastman. Used courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

In the course of his travels, Seth Eastman made drawings of the cities he passed through, along with other items not relating to the subject of his research. The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, has drawings by Eastman of Fairport Harbor and Sandusky, in addition to this one, of a grocer on the Cuyahoga River, in Cleveland.

After the initial discovery of this painting wore off, I started to suspect that the watercolor painting,

Lake Erie, From Cleveland, might have been made in the 1850s, based partially on his observations in the 1830s. I couldn't locate any works this early by Seth Eastman, and the combination of factors in this painting - the portrayal of the landscape and the presence of Native Americans, among others - just seemed too good to be true.

So I did more research. I found that the layout of the harbor is consistent with Cleveland in 1833. The number and nature of buildings corresponds reasonably with Whelpley's print of a year later. And the improvements made in the 1840s are not present. Further, the technique of the painting is not as refined as Eastman's later works.

I'm confident, now, that

Lake Erie, From Cleveland depicts Cleveland in July of 1833. It provides a rare glimpse into the landscape of this region as it used to be.

This watercolor is to be auctioned at

Sloans and Kenyon this Sunday. Their estimate is $80,000-$150,000 - meaning that the bidding will likely start at $40,000.

* The Seth Pease 1796 map of Cleveland (see

a drawing based upon said map) features a tent with a couple men situated by the mouth of the Cuyahoga River. However, this appears, to my eyes, to be merely added as a visual device, rather than an attempt to illustrate the location. For that reason, I don't count it as a painting of the city.

Correction: Janice B. Patterson, author of

Cleveland's Lighthouses, pointed out to me that where I said "breakwater", I meant "pier". I corrected the two instances of this term. She noted that "There were no breakwaters in the 1830s -- they were built in the 1870s. I think what you are calling a breakwater was actually just a wooden pier, built on pilings and possibly reinforced with stones."

![[Cleveland harbor]](http://farm9.staticflickr.com/8516/8414635606_e3049f77d0.jpg)