One of the first enclosed venues to watch a team sporting match was Case Commons, which, in 1868 had a wooden fence around the entire park. This innovation allowed field owners to charge 50 cents to attending fans, who came to support the amateur Forest City Base Ball Club despite the price. As a result, the sport of base ball flourished in the area. In fact, Cleveland hosted one of the first professional base ball teams in the country, in large part due to the fans willingness to pay to watch the sport.

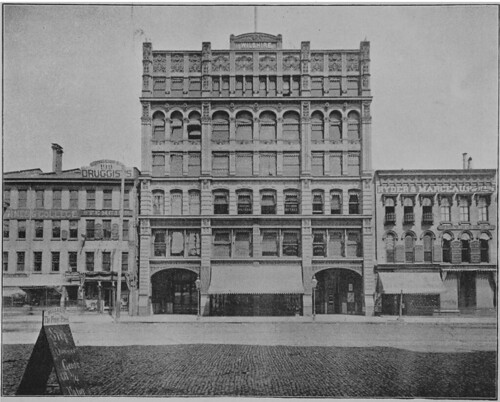

By the 1880’s, Cleveland had a contending base ball club, and the first

unofficial “booster” club formed, “Blackberriwyne Row”. The fans of this notorious club were christened as such due to their penchant for consuming vast amounts of blackberry wine during Cleveland Blues games, and cheering for their home club, while heckling the opposition. This is amusingly noted in a Cleveland Leader article, August 23rd, 1883:

“The necks were knocked off of several bottles of wine and many bumpers were swallowed to the success of the Gilt-edged [Cleveland Blues] on their trip West and East.”

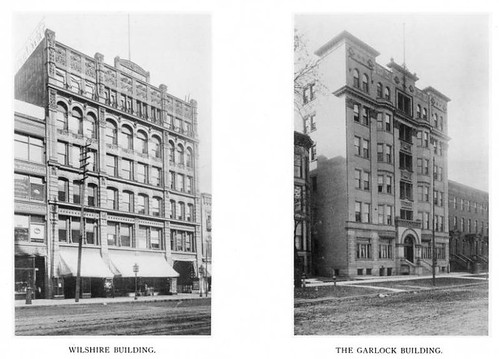

Members of the Blackberriwyne Row gang were influential Clevelanders. Al & Tom Johnson (future mayor of Cleveland), were prominent streetcar owners, while Charles LeMarche (Owner of Wedell House Hotel), George Wilson (Cigar Company Owner), and Mat Wolford (Tavern Owner), made up the leadership of the wine drinking hecklers, and were all major businessmen in the community. The club spearheaded an attendance that was 4th in the National League that year, 63,000 faithful souls in total.

As the population of Cleveland boomed, and the city attracted more professional sports clubs, attendance also rose, and Cleveland Sports Fan would become the backbone of sporting success in our town. On October 15th, 1915, 115,000 fans packed Brookside Park to watch the Cleveland White Autos v. Omaha Luxus for the National Amateur Baseball Championship. Cleveland also holds the title for largest attendance for a professional baseball game, when 84,587 loyal Cleveland fans packed Municipal Stadium to watch Bob Feller’s Indians.

Loyal Cleveland sports fans also packed stadiums and ballparks to witness the birth of the NFL. The fans outrage over Art Modell moving the Browns out of Cleveland in the 1990’s, resulted in an unprecedented move by the NFL to grant the city a franchise before an owner or stadium was in place.

Also during the 1990’s, Cleveland Indians fans set a Major League record of 455 consecutive sell outs of Jacobs Field from June 12, 1995-April 4, 2001. This amazing record was fueled by; a great team, enthusiastic fans, and the constant pounding of a drum at the games.

John Adams is the epitome of Cleveland Sports fan. On April 27th, he attended, and rallied the Cleveland Indians with his rally drumming, for the 3,000th game. This feat is unprecedented in sports, and an accomplishment that all citizens of Cleveland can be proud of. Adams exemplifies the historical spirit of Cleveland Sports Fan, and continues the proud tradition of the fans of Cleveland sports being the backbone of her professional and amateur franchises.

Sources:

Cleveland Leader

Base Ball on the Western Reserve, James Egan Jr.

Baseball Chronology

The Cleveland Blues Base Ball Club

Wikipedia

Photos:

1st Photo - Mayor Tom L. Johnson - Wikipedia

2nd Photo - Brookside Park, 1914 - www.cbbbc.webs.com

3rd Photo - John Adams - www.letsgotribe.com