Back in January, I identified this pair of historically significant homes in the Collinwood neighborhood of Cleveland, 15002 Sylvia Avenue (left) and 15006 Westropp Avenue (right). Both were built in the 1840s or 1850s, making them some of the very oldest in the area, and, to make them more significant, both seemed to have been built by the same builder, for the same family. The pair even made their way into Hidden History of Cleveland (History Press, 2011).

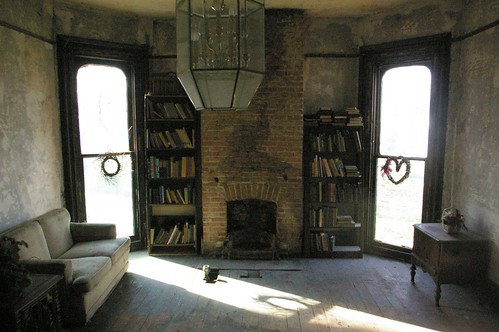

A few days ago, I saw that the one on Westropp Avenue had been condemned. I took a closer look. Someone had started to remove the aluminum siding. The yard looked overgrown. The doors had been broken down, presumably by city inspectors, seeking to gain access to the property. And there was a ton of stuff inside.

But did I see anything that really justified condemning the structure? No.

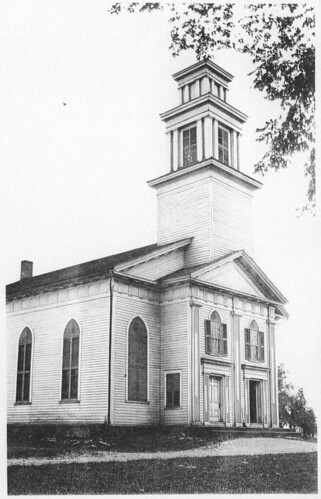

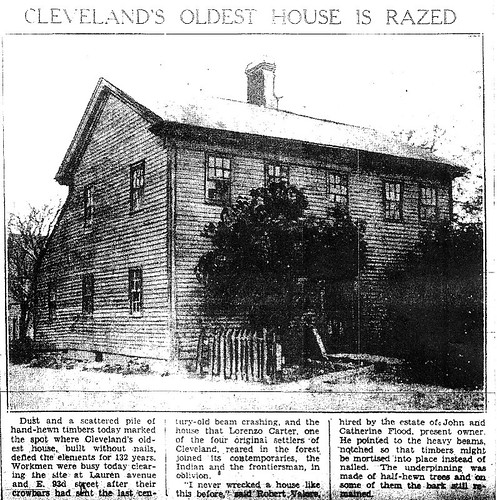

Photograph by I.T. Frary, from Ohio in Homespun and Calico, page 16.

Perhaps this photograph will make it easier to visualize the house as it was and may again be. The house in this photo is similar, save that the wing on our house was on the left side of the house and that ours has no second floor windows on the front of the house. There's a lot of great detail, I'm sure, hiding underneath the aluminum siding, cement shingles, and asphalt composition siding. How am I so sure of this? I'll reveal what I've been able to determine about original details in the structure later, once I've explained the history behind it.

The Dille and McIlrath families were some of the earliest settlers to the Collinwood area. They played a major part in the growth and development of the town.

1803(Wickham. The Pioneer Families of Cleveland, 1796-1840, pages 68-69.)

Dille

Ninety years ago, there was no family name in this locality more familiar than that of Dille, and no other family so numerically numerous. There were three separate branches of the Dille in the county, headed by two brothers and their nephew. David Dille, Jr., came in 1797 from Washington County, Pa., to spy out the land. He was a farmer and was looking for fertile soil upon which to locate. He did not find what he wanted in or near the hamlet at the mouth of the Cuyahoga, and finally decided upon a 100-acre lot in Euclid. This decision would seem to have barred him and his family from this local history, were it not that they sojourned six weeks in town while their log-cabin in Euclid was being built, and that the children and grandchildren intermarried into Cleveland families, so that David's descendants today - many of them of much local importance - are distributed over the length and breadth of this city. His brother, Asa Dille, Settled in East Cleveland, on Mayfield Road, and the nephew, Samuel Dille, Sr., on Broadway.

1803(Wickham, page 71)

Dille

Asa Dille, Sr., brother of David Dille, married Frances Saylor. His log-cabin was on Euclid Avenue, just south of Mayfield Road. When Cuyahoga County was organized in 1810, he was elected its first treasurer. His name appears in connection with societies organized in Cleveland for philanthropic efforts, but nothing else is found concerning him. He had ten children, nine of whom attained majority.

1803(Wickham, page 72)

McIlrath

There are many family reunions held every year in Cleveland, but none of them were organized so early or have so large a membership as that of McIlrath. Furthermore, this big clan has another point of superiority over others which is a matter of great local pride. Adult McIlraths in some of its branches, that of Alexander, for instance, can visit the McIlrath cemetery in East Cleveland and stand by the graves of their great-great-grandmother, their great-grandparents, and their grandparents, all of whom lived and died in that locality.

Can any Cleveland family beat that record?

...

One of the sons, Alexander, and his brother in law, John Shaw, came on in 1803, and each purchased 640 acres of land, much of it fronting on Euclid Ave., and extending north to the lake.

Samuel and Isabella McIlrath, the parents, started for East Cleveland in 1808. With other members of the family, they came in ox-teams, drawing household furniture, farming utensils, and the younger and frailer members of the party. They were six months making the journey, therefore must have traveled at their leisure. They settled in a log-house opposite Lake View Cemetery.

Abner C. and Eliza McIlrath kept a tavern on Euclid Avenue, in East Cleveland, where they lived all their married lives, and raised 13 children. Their four sons served in the Civil War, and their names can be read on the Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument on the Public Square.(Wickham, page 73)

...

It will be noted that the elder McIlraths, children of Samuel and Isabel, were middle-aged when they came to Cleveland. Andrew, the oldest son, was 50 years old; Samuel, his son, and fifth child, married in 1810, Betsy Carlton. Her maiden name was Davis, and she had Carlton children, Davis and Sherman Carlton - both fine men who removed to Elkhart, Ind.

Samuel McIlrath was address as "Squire" by the neighbors, and probably was a justice of the peace. Both Samuel and Betsey were warm-hearted and open-handed. There never was a time when their own household of children was not supplemented by tow or three children bearing other surnames, waifs who had lost one or both children in one of the fatal epidemics that occasionally prevailed.

Note: Pioneer Families of Cleveland is worth a look, if you're interested in the histories of these or any of the other early families of Cleveland - especially the ones that may not have received so much attention. The full text is available through Heritage Quest, one of the many databases that the Cleveland Public Library subscribes to.

The eldest of Samuel and Betsey McIlrath's children, Hiram (born circa 1814), married Katherine (or Catherine) Day (born c. 1812), daughter of Hiram Day (Wickham, page 73). By 1840, they had two children, Nancy (born c. 1837) and Morris (born c. 1839) (1850 U.S. Census). This growing family likely needed more space. To that end, in 1843, he purchased a three acre parcel from his parents, for $50 (Cuyahoga County Recorder, AFN: 184412120002). This is where he built the house, fronting on what is now East 152nd Street. A few years later, in 1853, he expanded the parcel by a half acre, for the same price again as the original purchase (Cuyahoga County Recorder, AFN: 185303210005).

The McIlraths were farmers, like most of families in the area.

One might presume that Hiram McIlrath would have built a house on this parcel as soon as possible - probably in 1844 - but the evidence suggests otherwise. The tax duplicates, available in the county archives, show Hiram's three acres being worth $26 in 1846 and $110 in 1848. The appropriate record for 1847 could not be located.

It's quite reasonable that the house was constructed in 1846, or possibly even 1845, and it just didn't make it onto the tax rolls. We know that it was built by 1848, so while we can't give an exact year, we can solidly place the date between 1844 and 1847.

By 1850, the value of their property had appreciated to $500 - a solid indicator of an improved house. Hiram and Catherine had had two more children, Cassius (born c. 1845) and Mary (born c. 1847).

Catherine McIlrath died, sometime between 1850 and 1856. By that year, Hiram had remarried. He and Mercy (or Mary) (born c. 1817) had two more children, Catherine E. (born c. 1856) and Harriet M. (born c. 1858) (1860 U.S. Census and Cuyahoga County Recorder, AFN: 185604290010). Their other children were not living with them at the time - it's not immediately obvious what became of them.

As of 1860, Hiram was justice of the peace for Euclid Township (1860 U.S. Census).

In April, 1856, Hiram and Mercy sold the parcel (3.5 acres) and the house to Samuel and Sarah McIlrath, for either $500 or $600 (Cuyahoga County Recorder, AFN: 185604290010). The exact relationship between Samuel and Hiram is unclear.

Eight months later, Samuel and Sarah McIlrath sold the property to Asa Dille, for $600 (AFN: 185612220011). Earlier in same year (May, 1856), Dille had purchased two other parcels - 93.25 acres, at a cost of $5,653.50 - from Samuel and Sarah McIlrath. The land was adjacent to this house. (The boundaries and surviving neighborhood farmhouses will be addressed in a future post.)

Polly (born c. 1797) and Asa (born c. 1782) Dille were farmers. While they'd been farming in this vicinity for quite a while, but with the purchase of the land from the McIlraths, they likely moved into this house. (They are adjacent to Thomas McIlrath in the 1860 U.S. Census - and the land his house is on is adjacent to this one on the 1858 Hopkins Map of Cuyahoga County.) Several members of the Dille family were laborers on the farm: Chas (born c. 1820); Darwin (born c. 1832); Henry C. (born c. 1838); Thos C. (born c. 1841); and Lucy (born c. 1834). It's unclear whether these were children or other relatives. One Fannie Dare (born c. 1839, a teacher, also lived with them at the time. The farm was said to be worth $8,000, and they had personal property worth $1,000 (1860 U.S. Census).

In 1867, Asa Dille's estate sold the property to Henry Westropp (Cuyahoga County Recorder, AFN: 186702220011). Henry (born c. 1813 or 1818) and his wife, Catherine (born c. 1822) immigrated to Ohio from Ireland in 1852 (1900 U.S. Census for Mary A. Westropp). As of 1870, ten of their children were living with them on this farm, said to be worth $8,000. The list on the 1870 U.S. Census notes: Mary A. (born c. 1842); Margaret (born c. 1850); Kate (born c. 1853); Ralph (born c. 1854); James H. (born c. 1856); John (born c. 1858); Patrick (born c. 1860); Bridget E. (Elizabeth?) (born c. 1862); William (born c. 1864); and Ellen (born c. 1866). Ralph, James H., and John worked on the farm with their father.

A decade later, Mary, James, Elizabeth, and William were still living on the farm. James was helping to run the farm while William was in school (1880 U.S. Census).

Henry Westropp remained in the house for the remainder of his life. The property was split among his heirs, after his death, in 1884. The fractional parts and splits are too numerous to document in the space available here.

In 1880, Catherine Westropp married William J. Busby (born March, 1852), an Irish immigrant who came to the U.S. in 1875. As of 1900, they occupied a house at 50 Westropp Road, adjacent to the house of her brothers, Patrick and John P, and her sister, Mary A. - 37 Westropp Road. The men were all farmers (1900 U.S. Census).

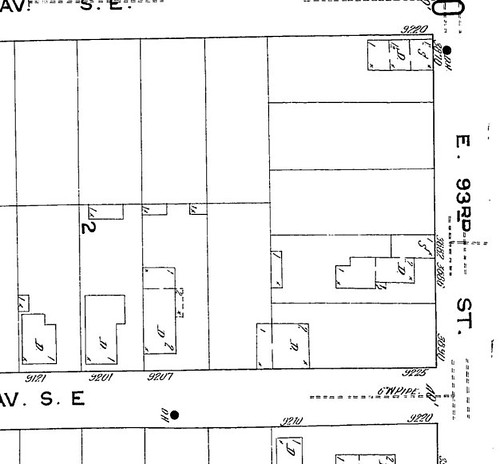

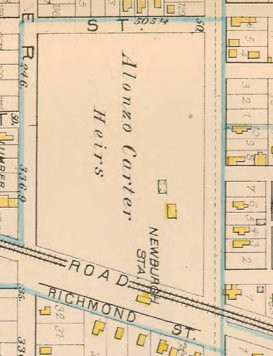

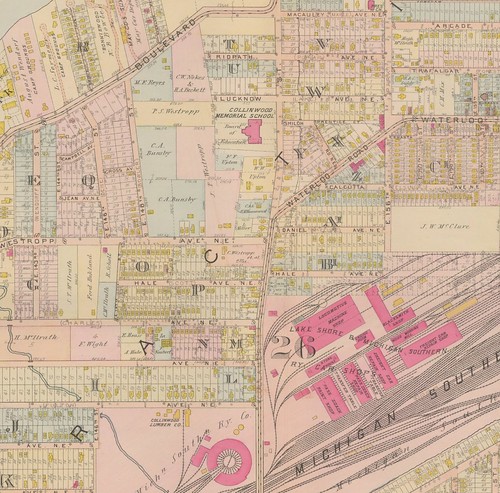

Detail, Plate 5, Flynn Atlas of the Suburbs of Cleveland, Ohio, 1898. Used courtesy of Cleveland Public Library.

In this map detail, north is at the top. Erie Street (now East 152nd Street) runs top to bottom. From left to right, at the bottom, is Scott Avenue (now Hale Avenue, and mostly covered by Interstate 90). The street north of Scott is now known as Westropp. Between these two roads is a parcel, labeled "Cath. A. Westropp et al. 2 35/100 A" - the yellow shape between "Cath" and "A." is our subject house - 15006 Westropp Avenue. On the other side of the road is a parcel belonging to John A. Westropp - this was part of the farm.

The yellow shapes with Xs on them are barns or other outbuildings. One was likely a carriage house, while others may have been for chickens or cows. The one on the north side of the road, running parallel to it, was two stories high - all the rest of the outbuildings that survived to 1913 were only 1 story (1912-1913 Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps for Cleveland, Ohio, Volume 8, Plate 13).

In 1910, Patrick S. Westropp, John P. Westrop, and Katherine C. Busby were all living in their childhood home, 15006 Westropp. Patrick was noted to still be working as a farmer (1910 U.S. Census).

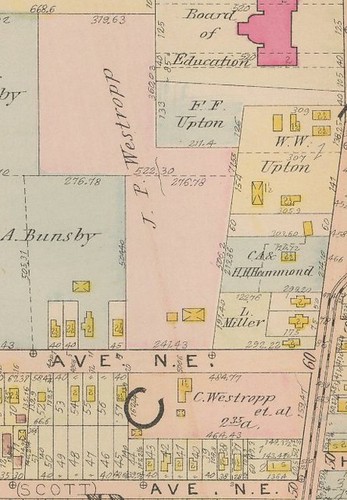

Detail, 1912 Plat Book of the City of Cleveland, Volume 1, Plate 40. Used courtesy of Cleveland Public Library.

By 1912, the outbuilding with the biggest footprint on the 1898 map was gone.

Detail, 1912 Plat Book of the City of Cleveland, Volume 1, Plate 40. Used courtesy of Cleveland Public Library.

A wider angle view illustrates how much the neighborhood had changed by that date. The massive Collinwood rail yards, with their associated roundhouse and other buildings sit imposingly to the south. The Collinwood Memorial School - the red structure to the north of our house - had been built. Almost all of the blocks had been platted for houses, many of which had been built. Yet slightly off-center, shaded in red and blue, remains the undeveloped farmland, owned by the Busbys and Westropps.

John P. Westropp died Sunday, October 10, 1915, at 15006 Westropp. A funeral was held at St. Joseph's Church on the 13th, and he was buried at St. John's cemetery (Cleveland Necrology File).

By 1920, part of the house was being rented to Frank Kays, a pharmacist (born c. 1882) and his wife Ida M. Kays(born c. 1882) Kays. The U.S. Census taken that year has Katherine Busby as a resident, along with a nephew, Harold Westropp (born c. 1906) and two nieces, Margaret M. Westropp (born c. 1908) and Henrietta A. Westropp (born c. 1908). The three were born in Indiana.

One Elizabeth Gregory evidenly also a tenant, judging from this entry in the Cleveland Necrology File, dated January 5, 1924:

Gregory-Elizabeth, wife of the late Thomas E. Gregory, sister of Mrs. Mamie McNeil, Mrs. Rose M. Edwards and Mrs. Clara George, suddenly at her residence, 15006 Westropp avenue. Funeral from late residence and St. Jerome's church, Lake Shore Boulevard, at 9 a. m. Wednesday.Though he is not listed in the 1920 Census, Patrick Westropp seems to have remained a resident of this house - at least he was at the time of his death, April 13, 1929. His funeral was held at St. Jerome's Church on Tuesday, April 16 (Cleveland Necrology File).

A husband and wife, Frank and Josephine Borkovac (both born c. 1872) rented part of the house as of 1930. Frank worked on a punch machine, in the steel industry, while Josephine worked cleaning private homes (1930 U.S. Census).

Henriette Westropp married John Martick. After the wedding, he moved into this house. Henriette lived here until her death, on July 31, 1934. A funeral was held at St. Jerome's Church, at East 152nd Street and Lakeshore Boulevard (Cleveland Necrology File).

Catherine retained ownership of the property - and probably lived here - for the rest of her life. In 1934, it was transferred to her nieces and nephews (Cuyahoga County Recorder, AFN: 193410090075). Her heirs sold it to Dewey and Edna Pettit, in 1944 (Cuyahoga County Recorder, AFN: 193711160003 and 194408030076).

The Pettits lived here for the rest of their lives. It wasn't until 1985 that the property transferred, through Edna Pettit's estate, to Richard L. Pettit (Cuyahoga County Recorder, AFN: 00021263).

Richard Pettit sold the house to James R. Major, in 1987 (Cuyahoga County Recorder, AFN: 00369967). In 2002, Major sold it to the current owners, Sandra H. King and Henry King (Cuyahoga County Recorder, AFN: 200207031082).

There's much more to be unearthed regarding all of the families who called 15006 Westropp home. I've only cut it as short as I have due to limited time.

Photograph by I.T. Frary, from Ohio in Homespun and Calico, page 16.

As I mentioned above, the original appearance of the house on Westropp was likely very similar to this one. A wing, similar to the one here, existed on left side of the house, when facing the house from the exterior, rather than the right, as on this example. It was removed between 1920 and the mid 1950s.

The lines of the Westropp house don't look so sharp, mostly due to several layers of material hiding the original lines - aluminum siding over cement shingles over asphalt composition shingles over the wood siding. I'm sure that with these removed, it would look a lot more appealing.

The front doorway probably looked like the one in Frary's photograph, with a massive pediment balancing the (visually) empty space on the second floor. Ignoring the space above the door, ours would have probably looked something like the entrance on the Brainard Residence (demolished 2010).

The front door itself was likely similar to, if not identical, to this original door, found on the first floor, south wall.

This moulding, a relatively common shape for the period, surrounds the front door and the sidelights (the small vertical windows on either side of the door).

In this shot, a wider angle, one gets a better idea of the look of the doorway. Note that the sidelights have been boarded up, and that a wall now covers some of the trim.

A large chimney runs through the center of the house.

To your right, from the entrance, is the parlor. The three windows in that room retain the original trim and paneling, as shown here. The large quantity of material left in the house prevented an effective wider angle shot.

The beams that make up the frame of the house protrude from the four corners - in each case, about 5 inches. They were covered, at the time of construction or soon after, trim with a rounded edge. At some later date, this was concealed with plaster.

In the basement, the beams, some hand-hewn, that make up the structure of the house, are still visible.

The massive chimney, perhaps five feet wide, which once provided heat for the house still remains. Wood beams were added later for support.

Structural elements are also visible on the second floor.

On the outside, this nice trim, part of the gable end, remains, hinting at what might be present underneath.

Overall, there doesn't appear to be anything especially wrong with the house, other than the level of debris, both inside and outside the house, and the half-removed aluminum siding. There isn't any evidence of water getting in, and there don't seem to be any structural issues. It's a solid house, with good lines, and plenty of historic interior detail.

What happens next?

I have not yet seen the list of code violations - I've requested these, and any other public records associated with the condemnation of the property, and I expect to have them in hand next week. I'll share them at that time.

While the busy intersection may not make this the best location for a private residence, it could work quite well for an office, I would think. That would as an excellent way to preserve the structure.

Historic photographs of this house or the surroundings would be most welcome, as would any additional history of this structure and the families that called it home.

This house, built by Hiram McIlrath, between 1844 and 1848, factored into the lives of two of the earliest families to settle this area, the McIlraths and the Dilles. To quote I.T. Frary (Early Homes of Ohio, page 61),

We build monuments to the memory of heroes. These structures are monuments erected by the heroes themselves.

Correction: The story previously referred to the outermost layer of siding on the house as being vinyl siding. It is, in fact, aluminum siding. While this may suggest the motivations for the removal of some of the siding, it does not change any of the other facts, nor the conclusions reached.