This house, at 1209 East 71st Street - just north of Superior - has been on my radar for a long time. In fact, it was the subject of one of my very first stories here.

Try to imagine the house as it was at the time it was built, 160 years ago. Remove the porch. The house would have sat on a rise, a couple of steps leading up to the front door. The windows on the front of the house, on the first floor, had a somewhat ornate trim, as did the front door. The windows, two over two, would have been flanked by shutters, perhaps in dark green, in contrast to the white of the house.

The color scheme might have been something along the lines of the Clemen N. Jagger residence, now at Hale Farm and Village. The first floor windows on the front might have had panels underneath, like this structure, or they might have been triple-hung - what I do know is that the original window trim extended downward to a line even with the bottom of the doorframe.

It was a simple structure, but with good proportions, on a relatively small (ten acre) lot.

On the exterior, the house has plenty to tell us. The foundation, now covered with a layer of paint, bears the tool marks of the people who quarried and cut it.

While most of the framing for the house was cut in a sawmill, the largest timbers were hewn by hand. One can be seen here, underneath a bit of trim.

A closer look at the front of the house illustrates the flush siding - an uncommon detail. One can also see, in the paint, the outline of the trim that originally flanked the windows - a helpful piece of information for the party that chooses to fix up this house.

This house plays a signficant role in illustrating the way this neighborhood changed and grew over time.

William Lewis was born on 3 April 1809, in Westport St. Mary, Malmesbury, Wiltshire, England. His wife, Mary Anne Ponting Lewis, was born 1814, also in England. In 1847, they immigrated to the United States with their four children: Thomas (born 1838); George (born 1840); Jane (born about 1842); and Edward (born about 1845). By 1850, they were farming in East Cleveland, Ohio. (Sources: Find a Grave records for William Lewis and Mary Anne Ponting Lewis, 1850 and 1860 US Census).

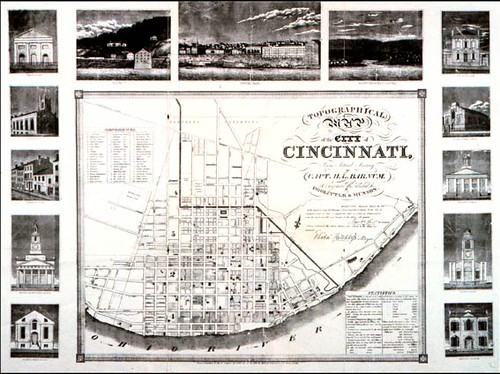

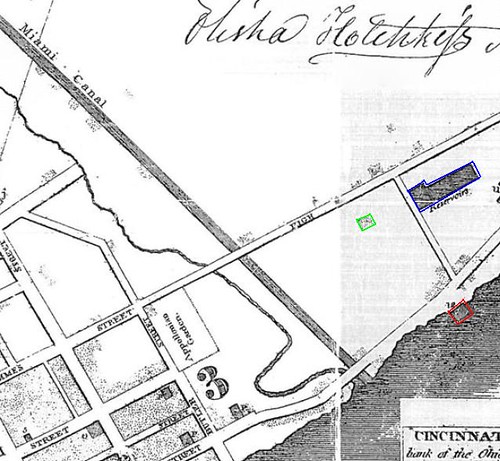

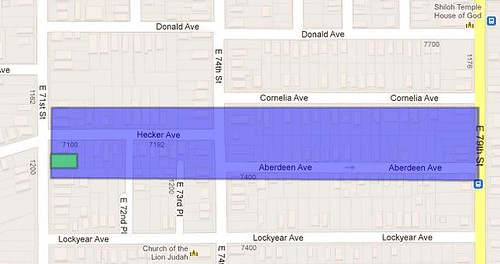

In September, 1852, they purchased, for $500, a ten acre parcel facing Becker Avenue - now East 71st Street. (Cuyahoga County Recorder, AFN: 185312190004 ) The parcel extended eastward to what is now East 79th Street. The original property is shown in blue on this map - the location of the house, in green.

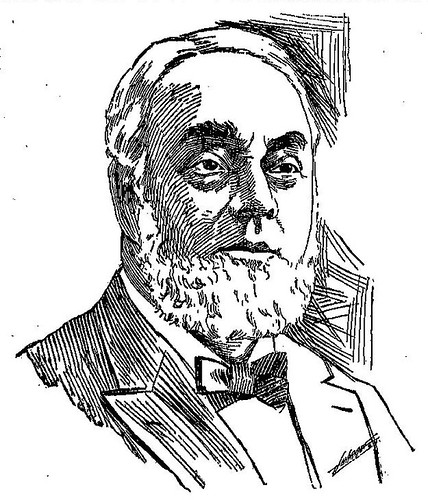

Published in the Cleveland Plain Dealer, 10 October 1897, page 4. Used courtesy of Cleveland Public Library.

The seller was one Edward Lewis, also from Wiltshire, England. He had risen to prominence within the iron and steel industry by the time this portrait was made, in 1897. His relationship, if any, with William Lewis is unclear.

At the price, it's plausible that the house had just been built - especially if Edward Lewis was a relative and was giving William a good deal. If not, the house was built soon after.

The 1860 US Census lists two more children: William (born about 1848) (henceforth William, Jr.) and Benjamin (born about 1851). It's unclear why William, Jr. wasn't numerated in the 1850 census.

William Lewis died July 30, 1854, at the age of 45. He was buried in Woodland Cemetery. I have not been able to locate any documentation as to the cause of death. (Find a Grave William Lewis.)

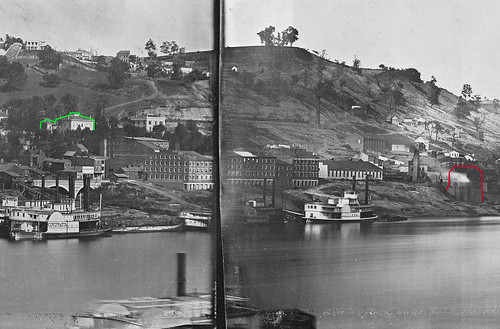

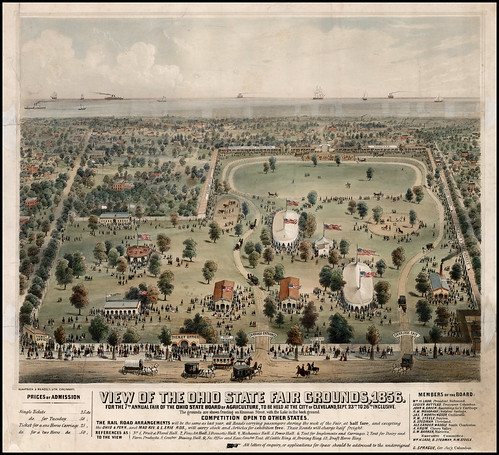

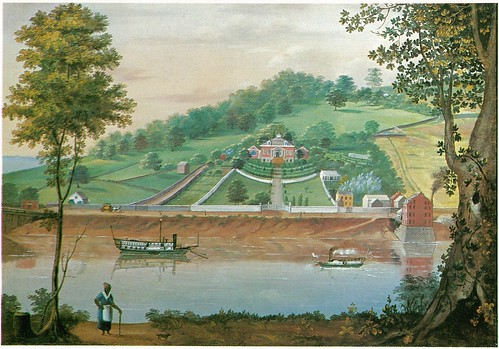

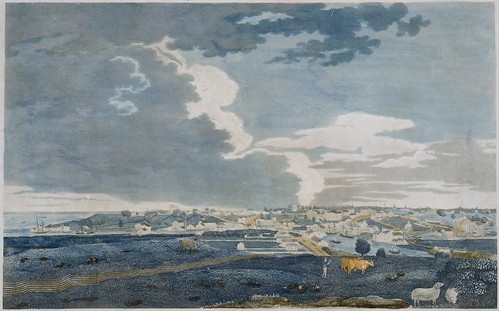

View of the Ohio State Fair Grounds, 1856. A hand-colored print (1856) by Klauprech & Menzel. Used courtesy of the Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps.

The family would have likely attended the 1856 Ohio State Fair, held just a mile and a quarter to the east.

By 1858, there were neighbors on either side, both occupying similarly sized (and shaped) lots. The family remained at this house, and by 1860, the value of the property was listed as $4,000.

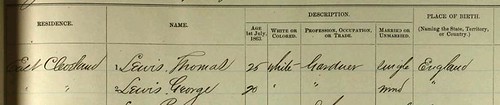

Used courtesy of the National Archives, Ancestry.com, and Cleveland Public Library.

Thomas Lewis and George Lewis both registered for the draft in 1863. Their occupation is listed as "gardener". How this is different from "farmer", which appears far more frequently, is unclear.

Mary Lewis died 11 December 1863. She was buried alongside her husband at Woodland Cemetery. (Find a Grave: Mary Anne Ponting Lewis)

George Lewis and Jane Lewis transferred their shares in the property to Thomas Lewis, in 1863. (Cuyahoga County Recorder, AFN: 186302250002)

Thomas Lewis married Amelia Gibbs. They raised several children in the house: Celia Jane Lewis (born 23 October 1865); Frank J. Lewis (born 1866); William E. Lewis (born July, 1870); Thomas E. Lewis (born 9 July 1873); Charles A. Lewis (born January, 1878); and Sarah E. Lewis (born December, 1879). Arthur Lewis, born November 1875, died the following month, from whooping cough.

By 1874, the area was becoming more developed. The Lewis children would have attended a brick schoolhouse, built at the corner of what is now Carl Avenue and Addison Road, a walk of abuot a fifth of a mile.

The larger farm lots were beginning to be split up to build residences. Some were massive, grand structures, like this house, at 6512 Superior, which I've written about in detail. (See: The best frame Italianate house I've seen in Cleveland and Threatened: The best frame Italianate house on Cleveland's east side)

On the opposite side of the street, the Beckenback residence has a similarly interesting story. Like the house facing it, it retains significant interior detail.

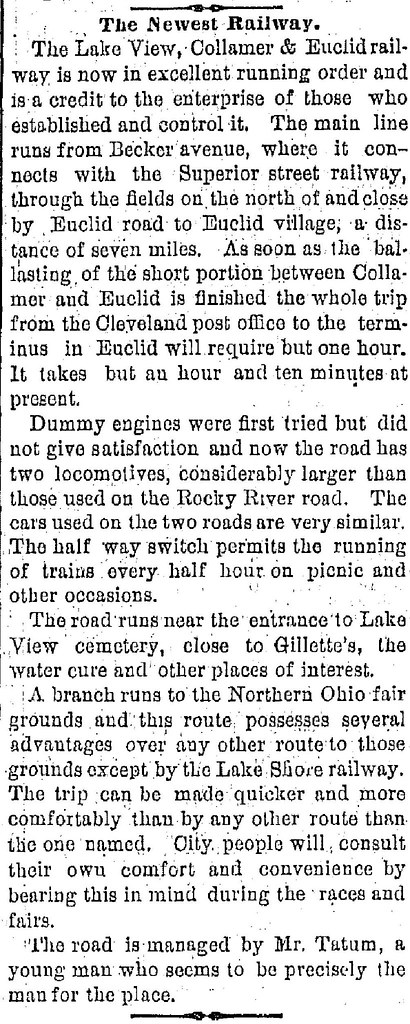

The biggest change to the immediate surroundings came in the form of the Lakeview, Collamer, and Euclid Railway, which ended just a couple hundred feet up Becker Avenue (now East 71st Street).

Published in the Cleveland Plain Dealer, 23 June 1876, page 4. Used courtesy of Cleveland Public Library.

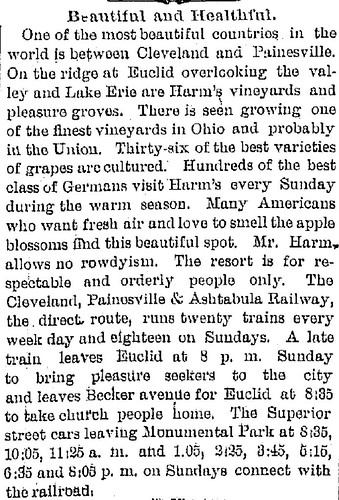

Published in the Cleveland Plain Dealer, 8 May 1880, page 4. Used courtesy of Cleveland Public Library.

Residence and Grounds of George Gilbert, Esquire, Euclid Station, Ohio. From the 1874 Lake Atlas of Cuyahoga County, Ohio. Used courtesy of Cleveland Public Library.

Passengers might have used the railway to visit Camp Gilbert, at the mouth of Euclid Creek.

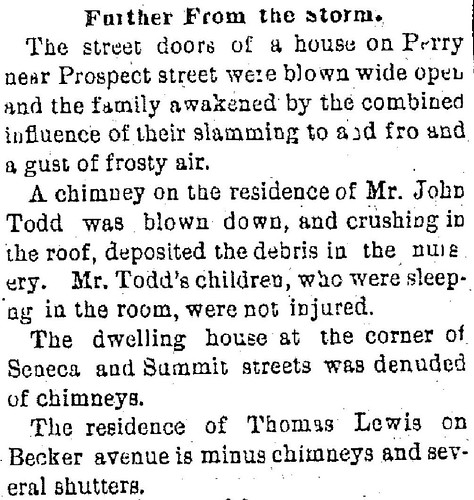

The following clipping, in addition to illustrating storm damage (front page news!) provides us with a vital bit of history - this house did, in fact, have shutters.

Published in the Cleveland Plain Dealer, 16 December 1876, page 1. Used courtesy of Cleveland Public Library.

Published in the Cleveland Plain Dealer, 10 February 1877, page 4. Used courtesy of Cleveland Public Library.

This quantity - an unknown portion of the Lewis flock - strongly suggests that at least part of their income came from selling either eggs or chickens.

Published in the Cleveland Plain Dealer, 13 April 1880, page 5. Used courtesy of Cleveland Public Library.

This purchase suggests that the railway was busy.

A beer garden was built at the railway terminal - next door to the Lewis house. As this 1885 article suggests, it caused some problems.

There's nothing useful that I can say about the following articles.

![1885-07-13-Page1]](http://farm6.staticflickr.com/5335/8766195163_b199fb9fc0.jpg)

Published in the Cleveland Plain Dealer, 13 July 1885, page 1. Used courtesy of Cleveland Public Library.

Published in the Cleveland Plain Dealer, 14 July 1885, page 1. Used courtesy of Cleveland Public Library.

Published in the Cleveland Plain Dealer, 14 July 1885, page 3. Used courtesy of Cleveland Public Library.

Published in the Cleveland Plain Dealer, 1 October 1885, page 3. Used courtesy of Cleveland Public Library.

In 1885, Celia Lewis married John Moser in a ceremony at the Lewis family home. John Moser moved in to the house, where they had two children: Grace M. Moser (born 1886) and John Lewis Moser (born 1887).

The Lewis / Moser family remained in the house through the end of the 19th century. The ten acre lot was gradually split into smaller and smaller peices, as this became a residential neighborhood. In 1900, Amelia Lewis sold the house to Eliza and William Lehmann. (Cuyahoga County Recorder, AFN: 190003230029)

In the next article, we'll see how this house (and the neighborhood) changed during the course of the 20th century.

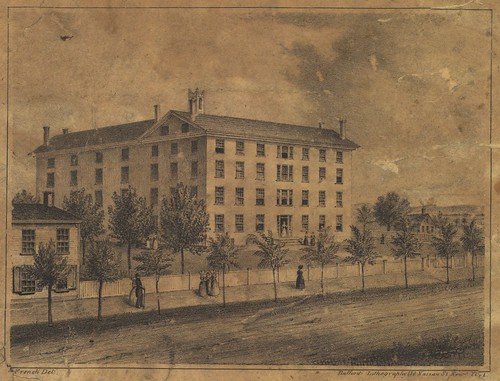

![[Granville Female College]](http://farm9.staticflickr.com/8550/8703957989_9b11da87b4.jpg)

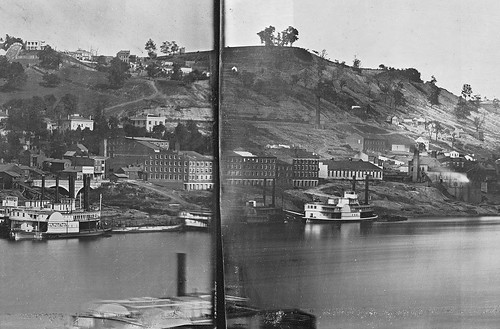

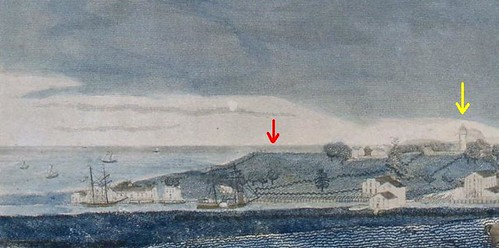

![[Cleveland harbor]](http://farm9.staticflickr.com/8516/8414635606_e3049f77d0.jpg)