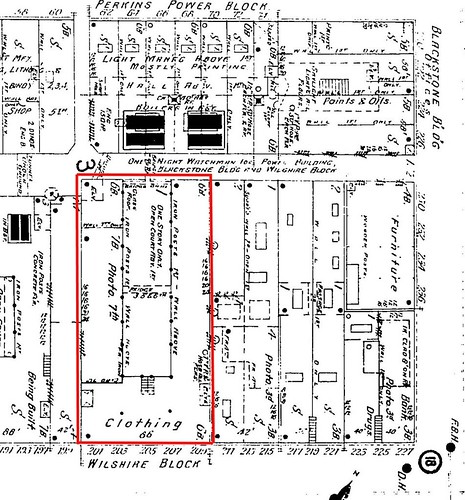

Note: This was originally posted on Wednesday, May 11, 2011. Due to an outage, the original file was lost. The text and images remain the same, but some of the formatting may have changed.

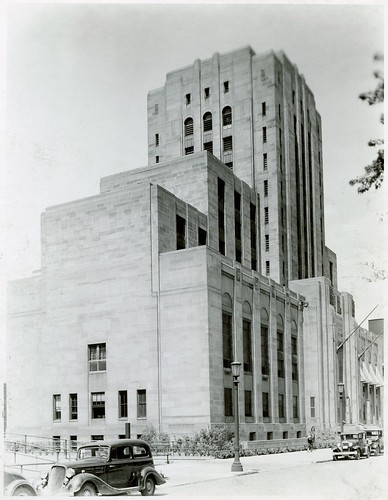

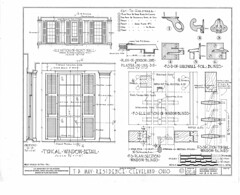

Photo courtesy of the Cleveland Landmarks Commission.

Photo courtesy of the Cleveland Landmarks Commission.

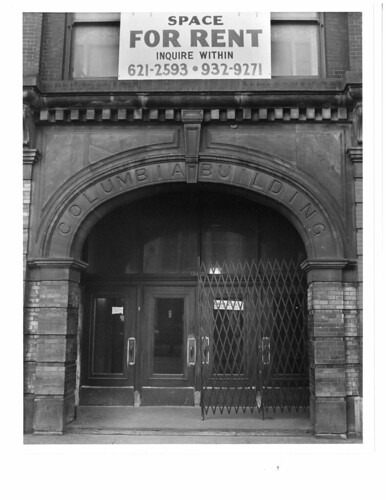

The Columbia building on Prospect-av. at E. 2d-st. stands alone as the only eight-story reinforced concrete building in Cleveland. It was the first to be built under the provisions of the revised building code. It was erected by M.A. Bradley, who has erected a number of other buildings during the past year. Cleveland Plain Dealer, December 26, 1909, page 25.

This new fireproof office building, now a

Cleveland Landmark, was designed by architect

M.E. Wells. It has been the home to many different businesses over the years. The most recent tenant was

David N. Myers University, who occupied the space from 1985 until the recent move to Chester Avenue and East 40th Streets.

The Columbia Building (112 Prospect Avenue, in downtown Cleveland) is threatened with demolition for a parking garage for the new casino. A report on the matter will be presented at the

Cleveland Landmarks Commission meeting tomorrow, Thursday, May 12.

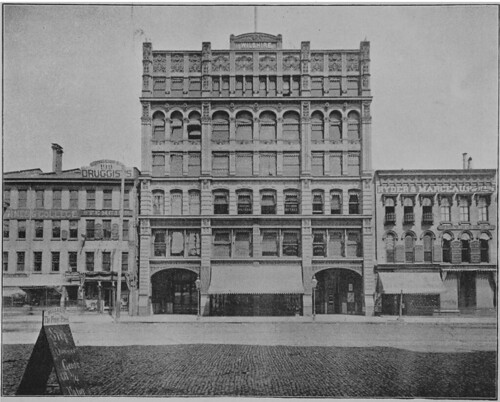

This 1909 photograph shows the newly-finished Columbia Building. The first floor featured plate glass windows and retail space yet unfilled. The photo was used in

an advertisement, published in the Cleveland

Plain Dealer on August 26, 1909, page 8.

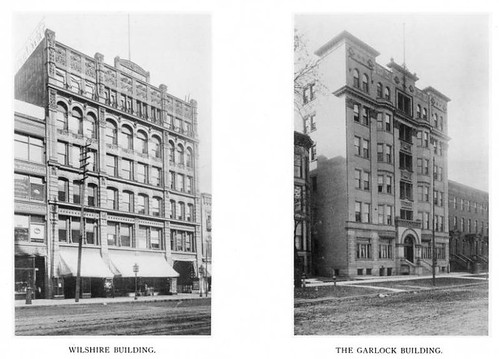

Another ad

Another ad, a detail of which is used here, extolls the virtues of the location - on the streetcar line and close to Public Square. It was published in the Cleveland

Plain Dealer on October 3, 1909, page 8.

The full history of this building is not known. It has been an office building since it was built, but the full tenant history remains to be investigated. It would be interesting to learn everything that might have happened within in these walls.

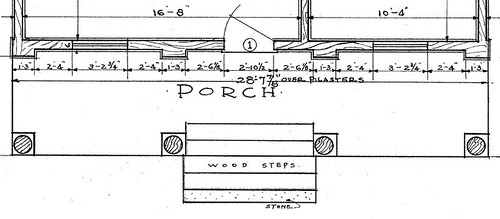

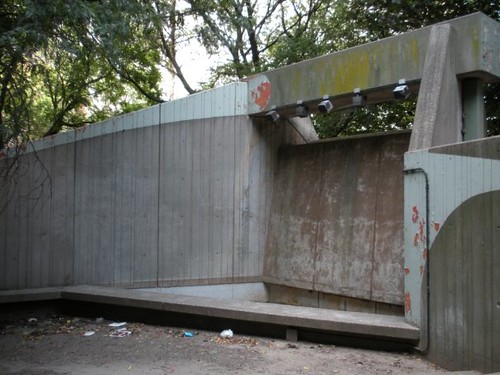

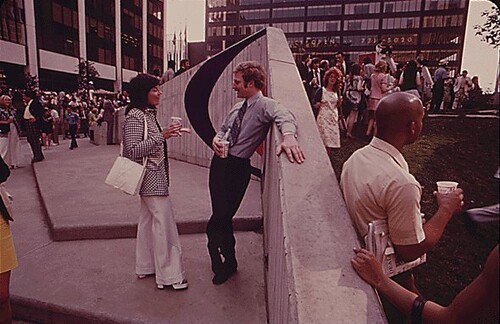

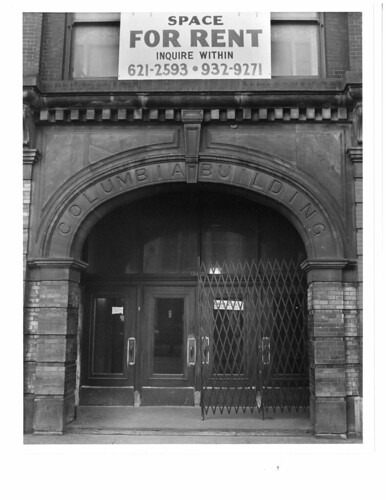

Photograph by Warner Thomas, City of Cleveland Bureau of Photographic Services.

Photograph by Warner Thomas, City of Cleveland Bureau of Photographic Services.

This 1981 photograph shows the entrance to the building, now marred by a less than pleasing awning. This could be remedied with relative ease.

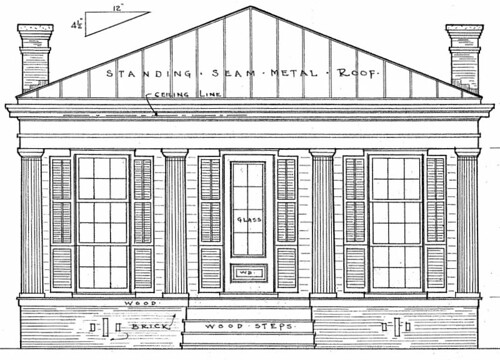

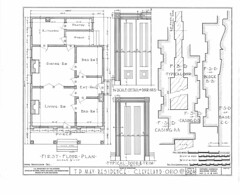

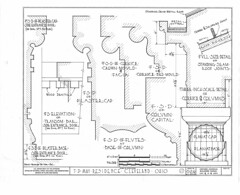

Courtesy of the Cleveland Landmarks Commission.

Courtesy of the Cleveland Landmarks Commission.

Some parts of the ornamentation surrounding the entrance can be seen in more detail here.

The building, while not as grand as some, is an attractive, solid structure, that contributes to the history of the city and the character of the neighborhood. It remains in good physical condition and could readily be used for any number of things.

You might ask, why, then, is it being demolished?

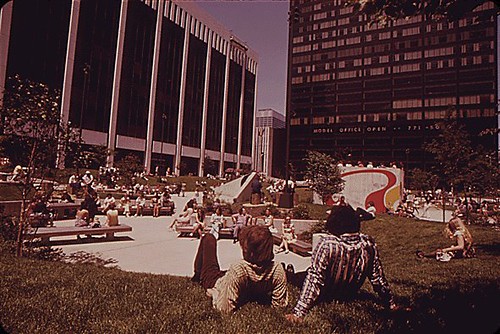

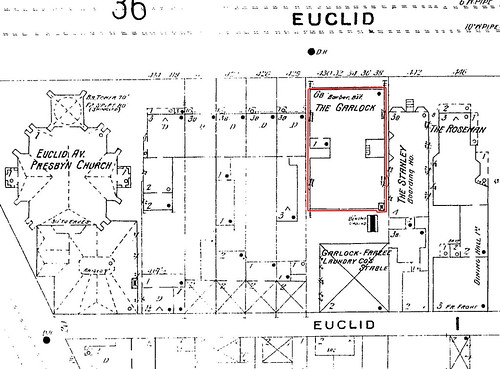

The demolition of this Cleveland Landmark will make way for this, the "welcome center" (parking garage) for the new downtown casino. This rendering shows the side facing Ontario. The older building in the center of the image is the

Stanley Block, one of the oldest commercial structures in downtown Cleveland, which, thanks to your efforts, was saved.

I really try to avoid architectural criticism. It's better left to people who are more knowledgable, like

Steven Litt. Further, I attempt to keep my opinions here limited to those surrounding history and historic preservation.

With that said, the proposed parking garage seems like almost as much an assault on the historic Stanley Block as

condemning it was. I see no attempt to make the new structure harmonize with the existing one. This could have been done through use of similar lines, or through similar materials, or through any number of other means.

It seems almost as if they're trying to make the Stanley Block stick out so much from the surroundings that the public will want it gone. Further, no attempt has been made to make it fit with the neighborhood. A design that would appeal to casinogoers could surely also make this concession.

How does this relate to the Columbia Building? Because the land the Columbia Building is standing on will be part of the parking garage.

I understand that parking is necessary.

But it seems stupid to replace a perfectly good building with a parking garage of questionable merit when there's a vacant lot but a block away that's being used for surface parking.

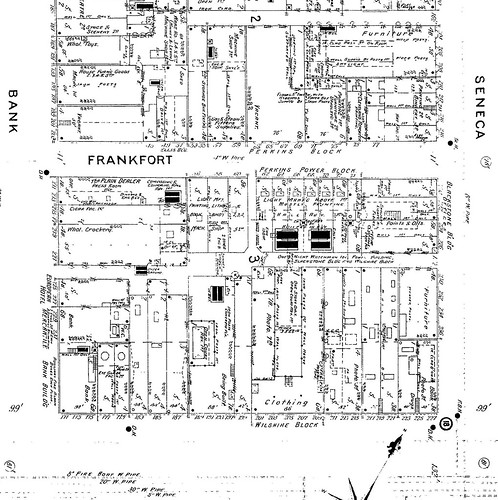

The lot in question is bounded by Prospect, East 4th, and Huron. It could be used for a combined parking lot for the Q and the casino. This would free up the lot utilized by the Q Arena on Ontario for use by the casino.

The plans may be found in

the agenda for the Cleveland Landmarks Commission meeting tomorrow, May 12, 2011. An archive of the plans can be found

here.

You may register your opinion either by appearing at the Landmarks Commission meeting tomorrow morning at Cleveland City Hall, at 9:00 am, or contact either Commission chair

Jennifer Coleman, Commission secretary

Robert Keiser (216-664-2531) or Councilman

Joe Cimperman (216-664-2691).