View Parks property in a larger map

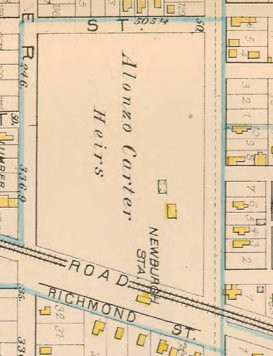

The Parks family farm, purchased in 1834, is indicated in this map in blue. It is bounded on the east by East 140th Street, on the south by Kuhlman Avenue, on the west by a diagonal that continues from the end of Eaglesmere to the lake shore, and on the north by Lake Erie. The farm, all told, was about 200 acres.

There’s a passage in the manuscript that really caught my attention.

They found later that the previous owner, a Colonel [John] Gardner and his family had nearly died there of chills and fever. Grandfather held the view, then common, that the disease was caused by a miasma that rose from the water and earth after nightfall and for many years the children were carefully herded into the house as it grew dusk. Anyhow, none of the family ever had a touch of it.

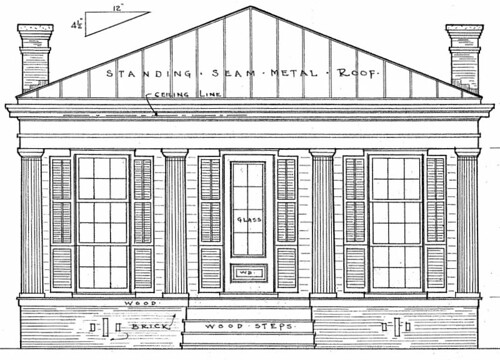

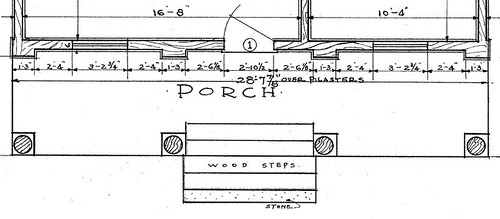

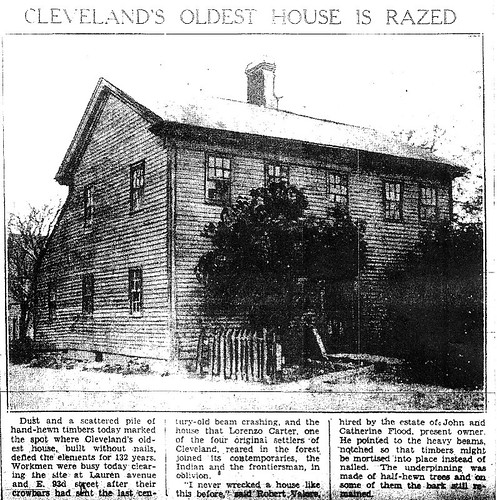

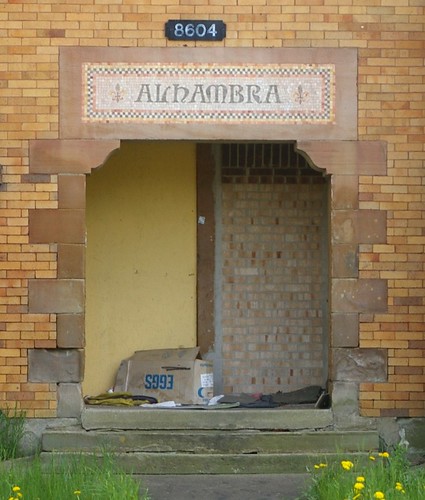

Perhaps that was because Grandfather's first act was to dog a big ditch right through the farm to the Lake; next he built a new house. The little old one was always used for a milk house.The milk house is noted by the jug of milk in the map above - right next to the site of the 1834 house.

I was a bit skeptical as to Gardner’s involvement with the property. I hadn’t heard accounts of property being rented - but research shows that it was not uncommon. In fact, evidence points to some very good reasons why John Gardner might have built the small, likely one-room house for his family on this piece of property rented from Henry Coit.

Achsa Sherwin was born December 28, 1789, in Winchenden, Massachusetts, the fifth of Ahimaz and Hannah Swan Sherwin’s ten children. She married John Gardner (born about 1789) on October 30, 1808, in Hartland, Vermont.

A decade after her marriage, Achsa’s parents moved to Cleveland. The account is described in Wickham’s Pioneer Families of Cleveland (p. 200-201).

On the morning of a bitter winter day in February, 1818, a large sleigh drawn by two farm horses moved briskly in a south-western direction from Middlebury, Vermont, a town but a few miles east of the New York state line, and about half-way between lakes Champlain and George.

The seat of this sleigh was occupied by Ahimaz Sherwin, Jr., 26 years of age, his young wife Hannah Swan Sherwin, and their little daughter Lucy but a few months old. The back of the sleigh was piled high with household furniture, bedding, and clothing. The family had started in mid-winter on a ride of 500 miles, at least half of which led through a trackless wilderness. But, aside from the weather, traveling at this time of year was far easier than through the summer months. A sleigh moved over the snow more smoothly and with less jolting than a wagon, also over ice-bound lakes and rivers that otherwise would have to be forded or avoided. The sleighing was excellent all the way, but the weather very severe; the thermometer for ten days of the trip was below zero. Their food and shelter for the night was ever uncertain, and a source of anxiety, for it depended upon little country taverns, or upon the hospitality of isolated farm-houses. It is ever a mystery to the woman of today how a mother managed to care for a babe and keep it warm on such a long, cold journey. The case of little Lucy Sherwin was not exceptional. Hundreds of very young children accompanied their parents to the wilds of Ohio when the journey was undertaken in the winter or early spring with the frost yet in the air, and snow still covering the ground. Furthermore, instances have been given where the pioneer party waited for an expected addition of a little stranger in a family, and then started on a trip two weeks after its arrival.

The Sherwins made the distance between Buffalo and Dunkirk on the frozen shores of Lake Erie, and, early in the evening of one day, their sleigh broke through the ice, thoroughly drenching its occupants. With their clothes frozen upon them, they had to continue their journey until a place was reached in which they could spend the night. The deep-seated cold that resulted from this mishap eventually undermined the constitution of the intrepid wife and mother, and although she lived several years after reaching Cleveland she never was again well, and died leaving three young children.

The journey ended March 1st - 18 days from the time it was started. No accommodation for them and their horses could be secured in the small village of Cleveland, and they had to turn around again and go back as far as Job Doan's tavern at Doan's Corners.

Luckily for Mr. Sherwin, Richard Blinn had begun to build a new house on his farm south of Doan's Corners, and on the road to Newburgh. He hired Mr. Sherwin to do the carpenter work on it, the Sherwins, meanwhile, living with the Blinn family. By the last of August, the house was finished, and the wages due Mr. Sherwin enabled him to return to Vermont and bring on his parents to share his pioneer home.Within a year or two, Achsa and John Gardner followed them west. (One of their children, Nelson Harvey Gardner, was born October 21, 1816, in Hartland, Vermont, fixing their residence in that place. By the time of the 1820 US Census, they were living in Cleveland.)

Gardner didn’t own any real estate in Cleveland until 1828, indicating that he either rented or lived with family or friends prior to that date, when he made a purchase on Seneca Street in downtown Cleveland (Cuyahoga County Recorder, AFN: 182812270001). He did not occupy the property immediately, as his family is still listed in Euclid Township in the 1830 US Census.

The Gardner family lived in this location while John Gardner operated a store on the east corner of Euclid Avenue and Noble Road.

Historic advertisements, included in Annals of Cleveland help illuminate the nature of the store and the sorts of things one would be able to buy in a village like this in the 1820s. They also help to show what sorts of things the residents of this area needed (or wanted).

June 4, 1824; adv:3/4 - John Gardner, has just opened a store in the town of Euclid, in the building formerly occupied as a store by E. Murray, Esq., deceased, consisting of a small but well assorted collection of Dry Goods, Groceries, and Hardware, which he will sell at reduced prices, for cash or approved country Produce.

Sept. 10, 1824; adv: 5/4 - Euclid Store. The subscriber has just received from two miles beyond the Eastward, a small but handsome assortment of Dry Goods, consisting of almost every article used in families, together with a good assortment of Groceries, of the first rate, and warranted. Also Codfish, Mackina Trout, of superior quality, Iron, Steel, Nails, Window Glass, 8 by 10 and 7 by 9, Soal and Upper Leather, Morocco Skins, With a variety of other articles, too numerous to mention - which will be exchanged for most kinds of Produce. Ashes will be taken in payment, if delivered at the ashery formerly occupied by Seth Doan, Esq. J. Gardner.

Dec. 9, 1825 ; adv: 3/5 - Euclid Store. J. Gardner. Has just received, and keeps constantly on hand, a general assortment of New Goods, consisting of Broadcloths, Cassimeres, Satinetts, Bombazetts, Calicoes, Chintzes, Cambrics, Plain and Figured Linos, Boot Muslins, Silk, Crapes, Velvets, Cotton and Worsted Vestings, Ratinetts, Salisbury & Plain Flannels, Silk and Cotton Flag Handkerchiefs, Tartan and Caroline Plaids, Cotton Ginghams and Checks, Cotton cloths, Cotton Yarn and Candlewicking, Men's coarse Boots and Shoes, School Books of all sort, New York Hats, Groceries, Crockery, Glass & Hardware, Iron. English Blister'd & Cast Steel, Drugs and Medicine, Paints and Dye·Stuffs, and other articles too numerous to mention. All the above articles are warranted to be of the first quality. He also pledges himself to sell as cheap as can be purchased in the country. Gentlemen and Ladies are requested to call and examine for themselves. Most kinds of Produce taken in payment. N. B. He also wishes to purchase a quantity of Black Salts, for part cash will be paid. Likewise, a quantity of dried Deerskins.

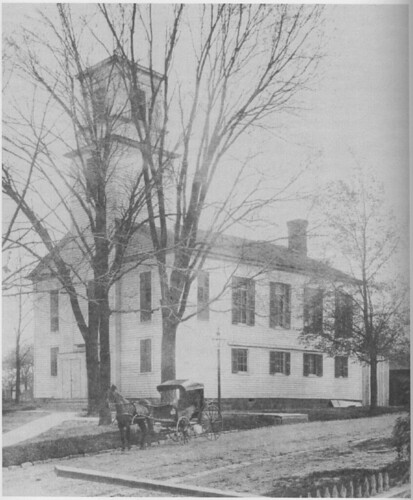

From Spiritual Pioneers; The Life & Times of First Presbyterian Church of East Cleveland, Ohio by Melinda Ule-Grohol, page 194.

Nov. 5, 1829; adv: 3/5 - For Rent. The subscriber offers for rent his Store and Store House in Euclid Township, a few rods west of the Presbyterian meeting house; he has built an addition to his Store, which makes it very large and convenient for a country Store. It is situated in a pleasant country for mercantile business which he will rent very reasonable; apply to the subscriber on the premises. John Gardner, Euclid.It’s unclear when Gardner’s store closed. The establishment reopened in 1830.

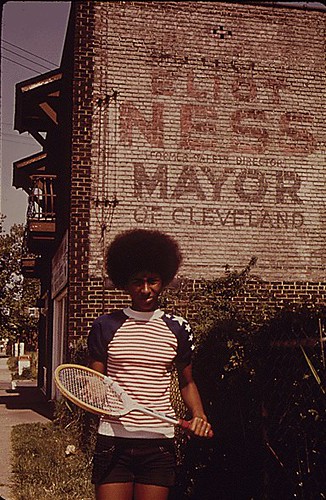

Nov. 11, 1830; adv:3/3 - Euclid New Store. New Goods at the lowest Cleaveland prices. H. Foote & Co. Have just opened a new store at the stand known as the Gardner store in the Town of Euclid where they have for sale a first rate assortment of Dry Goods, Groceries, Hardware, and Crockery.Within a couple years, Gardner opened a similar business in Cleveland.

Achsa Sherwin Gardner died in 1847, and was buried in East Cleveland Township Cemetery.

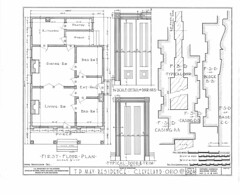

All six members of the Gardner family lived in what was likely a one-room house - on later maps, it shows up as less than half the size of the house with two rooms on each floor built by Sheldon Parks. From these cramped quarters, John Gardner travelled two and half miles each day to his store.

This is telling of the conditions endured by the early settlers to the region. It also illustrates that a path between the location on Euclid Avenue and the Parks farm was present at the time that they moved here, in 1834, providing a connection between their farm and the village.