Photograph by Carl Waite, April 28, 1936, for the Historic American Buildings Survey

Photograph by Carl Waite, April 28, 1936, for the Historic American Buildings SurveyI was browsing through the photographs and documentation for Cuyahoga County from the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS), the make-work project created in 1933 as part of the New Deal to record our country's most important historic structures. Three houses in Lakewood are included in this documentation. Two of them, the

Nicholson House and the

John Honam House (more often known simply as the Old Stone House) are still standing and are familar Lakewood landmarks. The third, however, I did not recognize.

According to the HABS documentation, the

Warren House was located in Lakewood at the intersection of Warren and Fisher Roads. There is no Fisher Road in Lakewood at the present. A Fischer Road exists, running east-west, south of Interstate 90, but it does not intersect with Warren Road. If it was continued east, the point where it would intersect with Warren would be in Cleveland, not Lakewood.

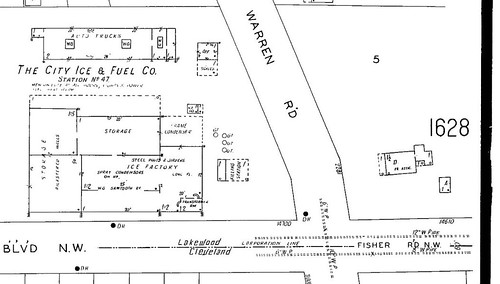

The 1914

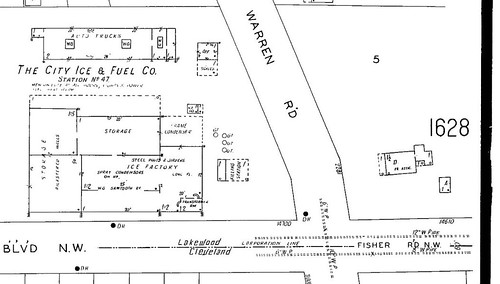

Plat Book of Cuyahoga County provided the answer. The map in question shows that the road now known as Lakewood Heights Boulevard was then known as Fisher. Further, it shows a brick, 1 1/2 story house on the northeast corner of the intersection, consistent with the Warren House.

This 1929 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map confirms that the building on the northeast corner of the intersection is, beyond a reasonable doubt, the Warren House. The outline of the house, which is very distinctive, matches exactly the outline given in the first drawing of the house in the

HABS documentation.

I wanted to know more about the house and its inhabitants. I contacted Mazie Adams, director of the

Lakewood Historical Society, who provided valuable research, including many sources that I would not have otherwise been able to check. I really appreciate her help on this project.

I haven't been able to learn much about the house or its inhabitants. While many sources that deal with Lakewood history recognize its importance, they are either unable to provide much information, or they provide information that doesn't check out. In this post, I'll try to illustrate what we do know.

Isaac Warren settled in this part of

Rockport Township in 1822, according to the sources for virtually all of our biographical information on the Warren family. (

Early Days of Lakewood, pages 29-30,

The Lakewood Story, page 71, and

Mrs. Townsend's Scrap Book,

page 9) Isaac Warren is said to have been a stockholder or investor in the

Connecticut Land Company. I doubt, as some say, that he was an "original stockholder", as there is no mention of his name in the index to

The Connecticut Land Company: A Study in the Beginnings of the Colonization of the Western Reserve (Claude L. Shepard, Western Reserve Historical Society, 1916.)

I find it to be more likely that he settled here in 1824, the year that Warren Road was put through, following an old Indian trail, between Detroit Avenue and Lorain Avenue.(

Early Days of Lakewood, page 69) I base this on his purchase of land from Garrit and Sarah Smith, of Watertown, Connecticut, in that year. (AFN: 182406250001) It is unclear whether Isaac Warren chose to settle here because of the road or if the road was built because of his interests.

Isaac Warren was from Waterbury, Connecticut. (AFN: 182406250001) He was married to Amelia Bronson, of New Bedford, Connecticut.

Mrs. Townsend's Scrap Book, page 9, provides the most complete account of their family:

They came overland from New Bedford, Connecticut. Mrs. Warren was Amelia Bronsen [Bronson] before her marriage, and had a great local reputation as an expert spinner of wool and weaver of homespun, which was the only cloth obtainable in those days. It was in fact "all wool and a yard wide". Mrs. Warren was born in Connecticut in 1799. Isaac Warren was a descendant of Dr. Joseph Warren of Boston who was killed in the Revolutionary War at the battle of Bunker Hill. Isaac Warren was a prominent citizen of the pioneer days and one of the biggest land owners, having several hundred acres. Mrs. Phelps is his only descendant living in Lakewood now. She lives on Clifton Boulevard with her daughter. Her son is married.

There were seven children born to the Warren Family; Sabra and Rebecca, daughters; John, Lucius, Abraham, Isaac and Sherman, sons. Lucius, Abraham and Isaac moved to Iowa and became large property owners. Sherman Warren settled in Missouri. Sabra married, Silas Gleason, son of pioneer Jeremiah Gleason, and Rebecca became the wife of John Johnson.

The only daughter of Rebecca, who for many years was regarded as mentally unbalanced due to a siege of scarlet fever, fell heir to all the Warren acreage. She was finally judged sane and left her estate to the Warren family, after giving a large slice to a German housekeeper who had cared for her in her last days.

There's a problem with this account, which is repeated in the other sources - that Isaac Warren was the son of Dr. Joseph Warren, who died in the Battle of Bunker Hill. The 1860 Census records Isaac Warren's birth in 1782, seven years after the Battle of Bunker Hill. Even if we discount the Census record, it is unlikely, though not impossible, that Warren would have married someone half his age. Joseph Warren could not have been Isaac's father. I suspect that either Isaac's father was another individual named "Joseph Warren" or that Dr. Joseph Warren was some other familial relation.

The remainder of the major facts from

Mrs. Townsend's Scrap Book are consistent with the other sources on the Warren family. Townsend goes into more detail than the others, and, unfortunately, didn't provide any footnotes as to the sources of her information.

Little other information exists about Isaac Warren and his family. The 1830, 1840, 1850, and 1860 U.S. Censuses place him in Rockport Township. He is listed as the property owner for part of the land (though not the site of this house) on the 1852 Blackmore and 1858 Hopkins maps. After that, I can find no record of him. There isn't any mention of his death in the

Plain Dealer, nor in the

Cleveland Necrology File. I've been unable to locate any property transfers that might suggest the dispersal of his estate or conveyance to his heirs. We can be reasonably sure that it was before 1874 - the

Atlas of Cuyahoga County, Ohio published that year shows his land having been split up to various parties.

Who was Isaac Warren? He was a reasonably well-off farmer. This is suggested by his land holdings and his house. He owned, at one point, at least 140 acres.

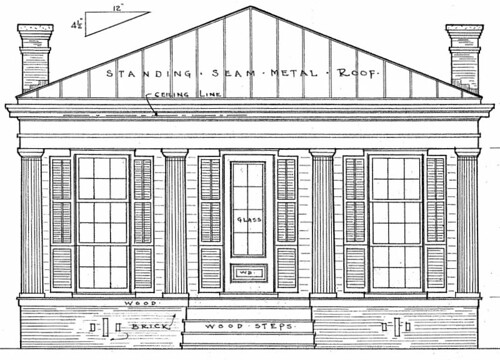

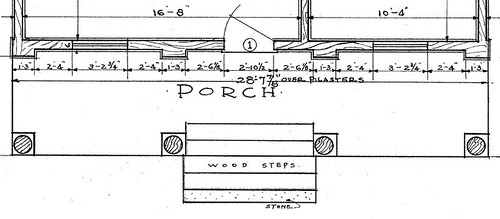

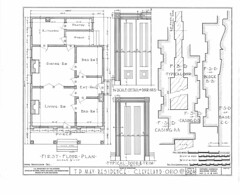

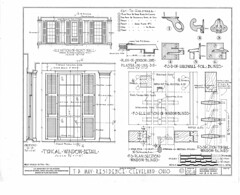

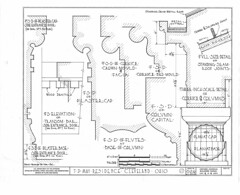

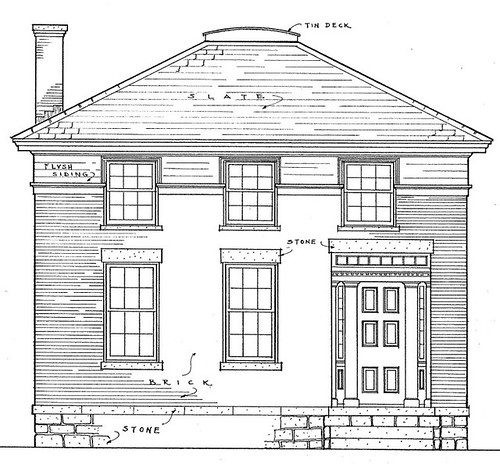

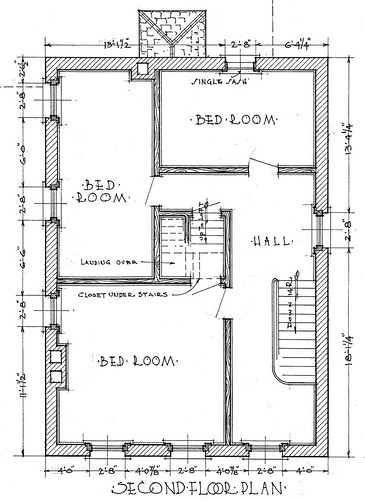

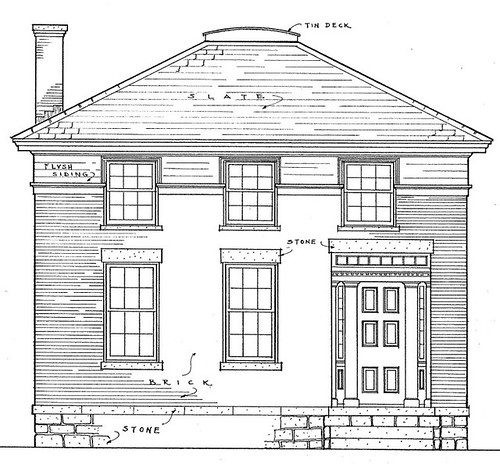

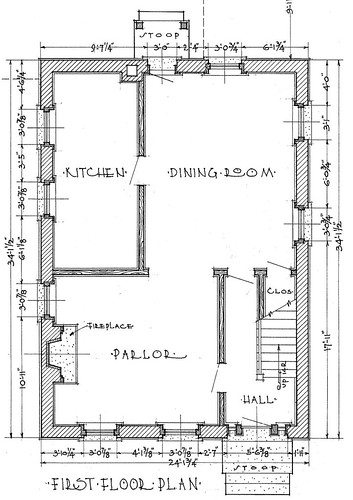

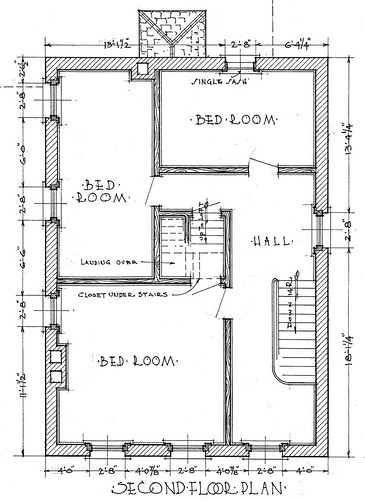

The Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS), in addition to the photograph above, provided detailed architectural drawings of the house. These include

exterior views, details of

mouldings and the front door, and

floorplans for the first and second floors.

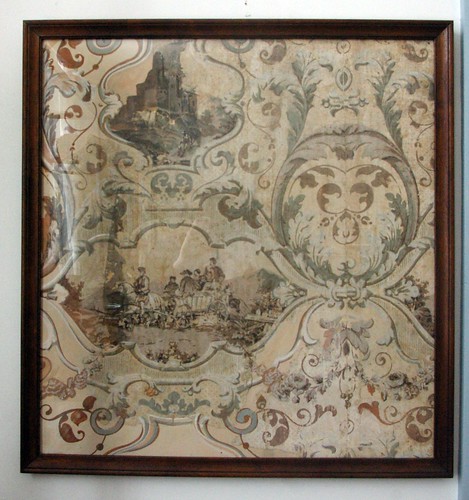

This detail view shows the exterior of the house as it appeared before the addition of the porch. The bricks were probably a raw sienna or ochre hue, rather than the red that we tend to expect, as that is the color of the clay in the immediate vicinity. (This is based on my experience growing up just down the street, near Alger and Lakewood Heights Boulevard.) This would have been consistent with the Price French residence, built in 1828 at the southwest corner of Detroit and Wyandotte. The French residence was noted to have been made from "mustard-colored" bricks. (

Lakewood by Thea Gallo Becker, Arcadia, 2003, page 10.)

The window sills were made of cement. The lintels were stone. The sloping part of the roof was slate, while the (nearly) flat part was tin.

The HABS chose to document the house because it was one of the oldest houses in Lakewood. They estimate the date of construction as 1835, though they note "Local historians and early owners are unable to shed much light on who the original owners and builders are." A similar assessment of the date is made in

Early History of Lakewood (page 77-78). The Survey's notes state that the walls were 13 inches thick, consistent with this date rather than a more recent one.

The front door is of a similar form, though more ornate than

the front door of the

Brainard residence, thought to have been built at about the same time. By the time of this 1936 photograph by Carl Waite for the Historic American Buildings Survey, the sidelights and transom surrounding the front door of the Isaac Warren residence had been filled in. It is illustrated in detail in

this rendering. The documentation of this as a significant architectural further reinforces the significance of the detail of the Brainard house and the need to preserve it.

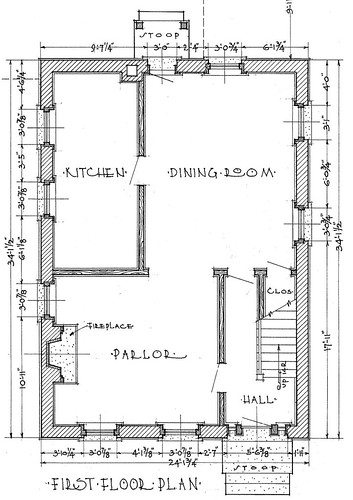

Each floor of the Isaac Warren residence was about 700 square feet. The drawings, details of

this one, done in 1936 by the HABS, help tell this family's story.

If you entered the house through the front door, you would be greeted by a hallway with a set of stairs going up to the second floor on the right. At the end of the hallway, a door led to the dining room. From this same vantage point, to the left, a door led into the parlor. The parlor, which measured about 13 x 15 feet, centered on a large fireplace, the primary source of heat in the house. A large open doorway joined the parlor to the dining room. The dining room, about 14 x 16 feet, provided plenty of space for the Warren family and any guests or farm laborers. The kitchen was connected by a door to the dining room. Another door off the dining room led outside. The ceiling on the first floor was 8'8" high.

The second floor had somewhat lower ceilings - 7'3" at the highest point. The stairs from the first floor led to a hallway with four doors. Three led to bedrooms. The fourth led to a winding staircase to a small loft.

The loft would have been a rather cramped space - about 4' high at the highest point. The dimensions of the space with a ceiling this high were about 20' x 5'. One might assume that this was also used as a bedroom.

The question remains as to when the house was built. It is shown on the 1858

Hopkins map, on a 44 acre parcel owned by J. Johnson. However, the map also illustrates a house on a larger parcel of land still owned by I. Warren. That house was located east of Warren Road, slightly south of where Westland Avenue now runs.

We know that Isaac Warren built a house when he first moved to Rockport Township, and that this one was built later. Could the house owned by Isaac Warren in 1858 have been the first house he built here? Or, might Isaac Warren's 1858 house have been built even later?

The 1830 Census shows 7 people in the Isaac Warren family. The 1840 Census shows 9. By 1850, the number was reduced to 3. I suspect that the house was built in about 1835, as has been suggested, as the family was growing and needed more space.

Another reasonable possibility is that it was built in the 1840s. The site of the house and about 25 acres of land were transferred from Isaac Warren to his son, John B. Warren, in 1840. (AFN: 184003030002) John Warren does not appear in the 1840 Census, yet by 1850, it had grown to 7 members. The house might have been built by him for his family.

In 1850, John and Ann Warren and four children (Catharine, Martha, Mary, and Lucy) were living in this house. Lucius Warren also lived with them.

Isaac Warren lived until after 1860. (1860 U.S. Census) Amelia Warren, his wife, died sometime before 1850. (1850 U.S. Census) I've been unable to locate obituaries or burial records for them.

John H. Johnson, a freshwater sailor born in New York, married Rebecca Warren sometime before 1850. (HABS, 1850 U.S. Census) In 1853, he purchased this house and 44 acres of land, north and east of the intersection of Warren Road and Lakewood Heights Boulevard, from John B. Warren and Ann Eliza Warren. (AFN: 185304160001) This is illustrated in the 1858

Hopkins map of Cuyahoga County. He worked the land as a farmer. (1870 U.S. Census) John and Rebecca had one child, Henrietta, born circa 1860.

Very little information exists regarding Johnson. He isn't mentioned in the chapter of

Early Days of Lakewood titled "Late Pioneers, 1840-1865" nor in 1865-1889 chapter. The HABS documentation provides some notes as to John Johnson's family, according to oral history. "Mr. Johnson's folks resided on Johnson Street, also known as Water Street in Cleveland, Ohio. Mr. Johnson's cousin and Nettie Johnson, a Cob Girl, operated a sanituarium at Green Springs, Ohio. There is a Johnson Homestead at Green Springs." I haven't been able to put this information to any use.

By 1874, their holdings appear to have increased to more than 60 acres, as shown on the

Atlas of Cuyahoga County, Ohio. At least some of this increase was likely due to the dispersal of Isaac Warren's estate. It's worth noting that on this map, as well as maps published in

1892 1898, and 1903 Rebecca P. Johnson is listed as the owner of the property, not John H. Warren. In the 1898 atlas, their property is divided into two, a

north part south half. The same is the case for the 1903 atlas - there are

north and

south parts. The land the house was on is in the northern part.

Rebecca Johnson died between 1870 and 1880. (1870 and 1880 U.S. Censuses) I have been unable to located an obituary or burial record for her. This makes her being listed on the maps as the owner of the land more curious. She was, in fact, the owner of at least part of it - a 1904 property sale lists Henrietta as the sole heir of Rebecca Johnson. (AFN: 190405130005)

John H. Johnson died in the residence, on the morning of February 17, 1905. A funeral was held in the Congregational church at Kamm's corners, at 2pm on Sunday, February 18. John Johnson was buried in Alger Cemetery. (Cleveland Necrology File)

Henrietta Johnson remained in the Isaac Warren residence for the rest of her life. (1880 and 1900 U.S. Census) In the early 20th century, the parcels of land around the house were gradually sold off. This is shown in

this plate from the 1914

Plat Book of Cuyahoga County. It also illustrates that several outbuildings were present around the house, including two that were 1 1/2 stories high.

Henrietta Johnson died in the Warren residence on October 6, 1917, at 6:45pm. The address of the house was listed as 2281 Warren Road. The funeral was held at her late home on Tuesday, October 9, at 2pm. Henrietta was buried in Alger Cemetery.

The status of the house after Henrietta Johnson's death is difficult to decipher. I haven't had any luck tracing the property transfers during the 1920s and early 1930s. This is due to the rapid split of the parcels in the area into residential lots and the transfer of the property among various entities due to foreclosure in the early 30s.

Perhaps these fragments will be of use to some future researcher.

Cadillac 7 pass tour.; good tires and motor; will sacrifice for $250; sell quick; can be seen at 2281 Warren rd., Lkwd.

Plain Dealer, May 11, 1926, page 25

Hennie-Alice Evelyn, beloved daughter of John and Coral (nee Fretter), sister of Charles, George, Mildred, Pearl and Mrs. Frank Burbank, Thursday, May 26. Funeral services at the late residence, 2281 Warren road, Lakewood, Saturday, May 28, at 1:30 p. m

Cleveland Necrology File

Mr. and Mrs. Grover C. Weed, 1388 Brockley Avenue, Lakewood, announce the marriage of their daughter, Ruth, to Mr. Francis Chambers, son of Mr. and Mrs. Frank Chambers, 2281 Warren Road, Lakewood, which took place Dec. 5, 1931.

Plain Dealer, October 10, 1932, page 33.

We Carry Triple-X Soil-Bil-Der and all othre Stadler Fertilizers. Also the complete line of Nursery Stock.

Brown & Son Nursery

Warren and Fisher Rds. - LAkewood 1957

Plain Dealer, April 26, 1936, page 23

Brown & Son's sign can be seen painted on the side of the house in the lead photograph. By 1938, they had moved to 18240 Detroit Avenue (

Plain Dealer, March 12, 1938, page 21) where they remained until 1962. (

Plain Dealer, June 22, 1962, page 54)

The property was sold at sheriff's sale in 1936, where it was purchased by Bertha H. Gund. (AFN: 193603230012) In 1938 John J. Gund and Bertha H. Gund sold the property to Field, Richards and Shepard, Inc. (AFN: 193803100082) The transfer included an interesting provision:

"Excepting, however, and reserving to the Grantor the brick house and wooden shed now on said premises (but not the land on which they are situated), together with the right to enter upon said premises and remove said house and shed at any time within thirty days from and after the date hereof; provided, however, that if said house and shed are not removed from said premises within said thirty day period, title thereto shall pass to and vest in the Grantee..."

This house feels familiar to me. I can't quite place it. This provision makes me wonder if it was moved, and I have, in fact, seen it somewhere else. Mazie Adams, director of the Lakewood Historical Society, checked the permits at city hall, but was unable to locate either a demolition or moving permit for this address.

Later in 1938, Field, Richards and Shepard, Inc. sold the property to the Standard Oil Company. (AFN: 193806040032) A gas station was built on the site soon after.

The gas station, Meme's Sohio, at 2285 Warren Road, can be seen in this 1956 photograph, used courtesy of the Cleveland Memory Project.

This wider view, also from 1956, provides a bit of a feel of the neighborhood at the time.

The property has since become a rental car agency.