Cleveland's Euclid Avenue isn't the main thoroughfare that it once was. Most of the grand homes that once graced it are now long gone. However, in conjunction with the creation of the Health Line, much has been lost. More of the historic fabric will be gone, if we don't act soon, just like the historic Cobb & Bradley building, shown here.

This post is an attempt to identify what we've lost (or may lose) along Euclid Avenue. It focuses on historic buildings that have been lost in the past couple years, or, in the case of structures still standing, those that face immediate danger. Are all of these great architecture? Perhaps not - but they contribute to the streetscape and to the shape of our community.

Our journey will begin east from downtown Cleveland.

Photo by Keri Zipay

Photo by Keri Zipay The terra-cotta-faced Cleveland Cadillac Building, at 1935 Euclid Avenue was built in 1914. Knox and Elliott were the architects. It was demolished by Cleveland State University to make way for expansion.

The Student Center at Cleveland State University, designed by Don Hisaka was also demolished, to make way for another structure serving the same purpose. Many said that the structure as it was was utterly unusable. Perhaps it was. How do you deal with a visually stunning structure when it doesn't do the job it's supposed to do?

Photo by Pavel Dyban

This group of four buildings were located on the south side of the street, immediately east of the train tracks and East 55th Street. They have all been demolished. When the photo was taken, it seems that an additional building, immediately to the east, had been recently demolished. The third building over appears, based on the lack of windows, to have been some sort of secure storage facility.

Photo by Otterphoto

The Cobb and Bradley building was on the north side of the street, between the trestle and East 57th Street. The late 19th century architectural detail is more of an earlier era than most of what was present on this part of Euclid Avenue. It was demolished in April of 2009.

Photo by Otterphoto

Immediately to the east lay this apartment building, which was demolished at the same time. It's interesting that most of the copper detail around the roof still remained when this photo was taken.

Another building was present on the north side of Euclid Avenue, between East 57th and East 59th Streets, but I have been unable to locate a photo of the structure.

Photo by Pavel Dyban

Of the three commerical / industrial buildings photographed here by Pavel Dyban in November, 2005, during his cross-country road trip, only one survives. The block looks like a single building, but is actually three. The rear part, as well as the building closer to us have both been demolished.

Photo by Pavel Dyban

The remaining structure looks somewhat naked. The façade of 6611 Euclid was removed when the road was widened, to accompany a turn lane (as was required) when the Health Line was built. Another building, also now lost to history, stood adjacent to the east.

Continuing east on the north side of the street is the Dunham Tavern, the oldest structure on its original foundation in the city.

Photo by Pavel Dyban

Immediately east of the Dunham Tavern, at the northeast corner of Euclid and East 69th Street was this two-story commercial structure, which has been demolished.

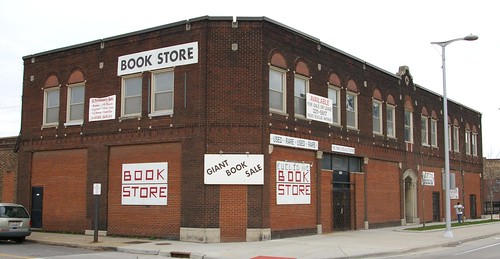

Immediately opposite, on the south side of Euclid Avenue, sat the two story brick building that housed The Two Dollar Rare Book Store. While the building itself was relatively undistinguished, the bookstore was phenomenal. I've never seen so many great books at such reasonable prices. Chris Uram, the owner, took in the books that other book dealers wouldn't touch, because they were often in such poor condition. He offered them at bargain prices. Hundreds of them made their way to my house. I do hope that he is able to relocate.

The Eton and Rugby Hall Apartments, at 7338 Euclid Avenue, were built 1925. George Allen Grieble was the architect. These buildings, with their beautiful terra cotta details have been vacant for at least 30 years. They will be demolished soon to make way for low-income senior housing.

The Cleveland Play House was remodeled in 1983 by Philip Johnson, the architect best known for his 1949 Glass House, a National Historic Landmark, in New Canaan, Connecticut. Johnson is a Clevelander, and this is the only building by him in this city.

The structure has been purchased by the Cleveland Clinic. While they have not yet revealed their plans for the structure, I strongly suspect, given their track record, that it will be demolished.

Euclid Avenue Congregational Church 9606 Euclid Avenue, was built in 1884-1887. The architects were Coburn and Barnum. It was demolished, following a fire caused by a lightning strike in the early hours of Tuesday, March 23.

Photo by Thom Sheridan

The original Hathaway Brown School building, on the north side of Euclid Avenue, at East 97th Street, was designed by architects Hubbell and Benes in 1905. It was demolished in January by the Cleveland Clinic.

The original Laurel School building had been connected to the Hathaway Brown structure, and was demolished at the same time.

Were these buildings too far gone to be saved? For some, the answer is yes. Others could have been easily reused if the owners had chosen to. There's one, however, that I believe should be saved.

It's been defaced, as I indicated above, and what remains isn't terribly architecturally distinguished. That doesn't stop it from being important.

6611 Euclid, the tall industrial building standing here next to the Dunham Tavern, provides real context for the museum. It illustrates how the city grew up around this tavern, and the level of development threats faced by it. It hints at how close the tavern might have come to being demolished itself.

This historic structure, 6611 Euclid Avenue, was condemned on May 7. Do we want another vacant lot, or do we want something that contributes significantly to the Dunham Tavern Museum?

It's the last of the taller structures of its type along Euclid Avenue, between East 55th and East 105th Streets. Once it is gone, this context will be lost forever. The building is owned by the RTA - in other words, us. We need to make the right decision here.